Etherborn review

There’s an expectation with a puzzle game that it will challenge you and force you to think differently to obtain the solution. The very best of the genre do this, but also place the solution in plain sight by carefully establishing the rules and the language that the puzzle will operate under. Recently The Witness did this with staggering effect, each puzzle with a different key to solve it, be that through spatial awareness, logic, aural patterns, even careful observation of the surroundings. Etherborn tries to do this also by utilising a very interesting mechanic whereby your spatial perception is challenged in a variety of ways, however, as you progress through the challenges a couple of poorly explained changes as well as a fixed camera that actively works against you, ensures that solving the puzzles feels a little more like dumb luck than the elation of finally reaching the solution.

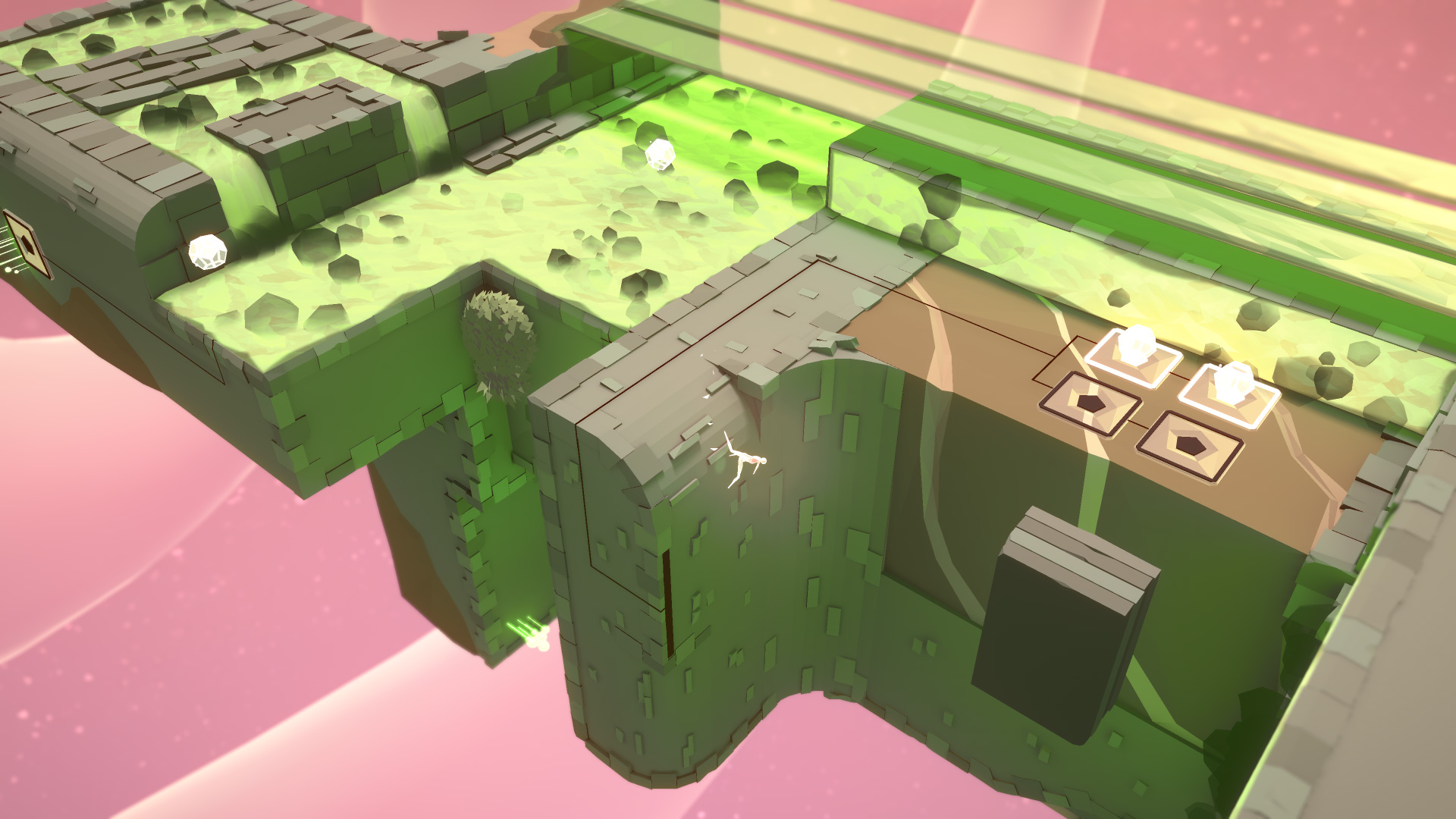

You play as a faceless and nameless entity in humanoid form with a disembodied voice narrating a confusing tale of origin and purpose. The story, such as it is, feels a little unnecessary, however, the metaphysical themes that run through the narration do mirror the substance of the puzzles. In Etherborn, gravity doesn’t work quite in the way that you would expect it, much like how a Mobius strip or the drawings of Escher challenge your perceptions of what is up and down, so too do the environments of Etherborn.

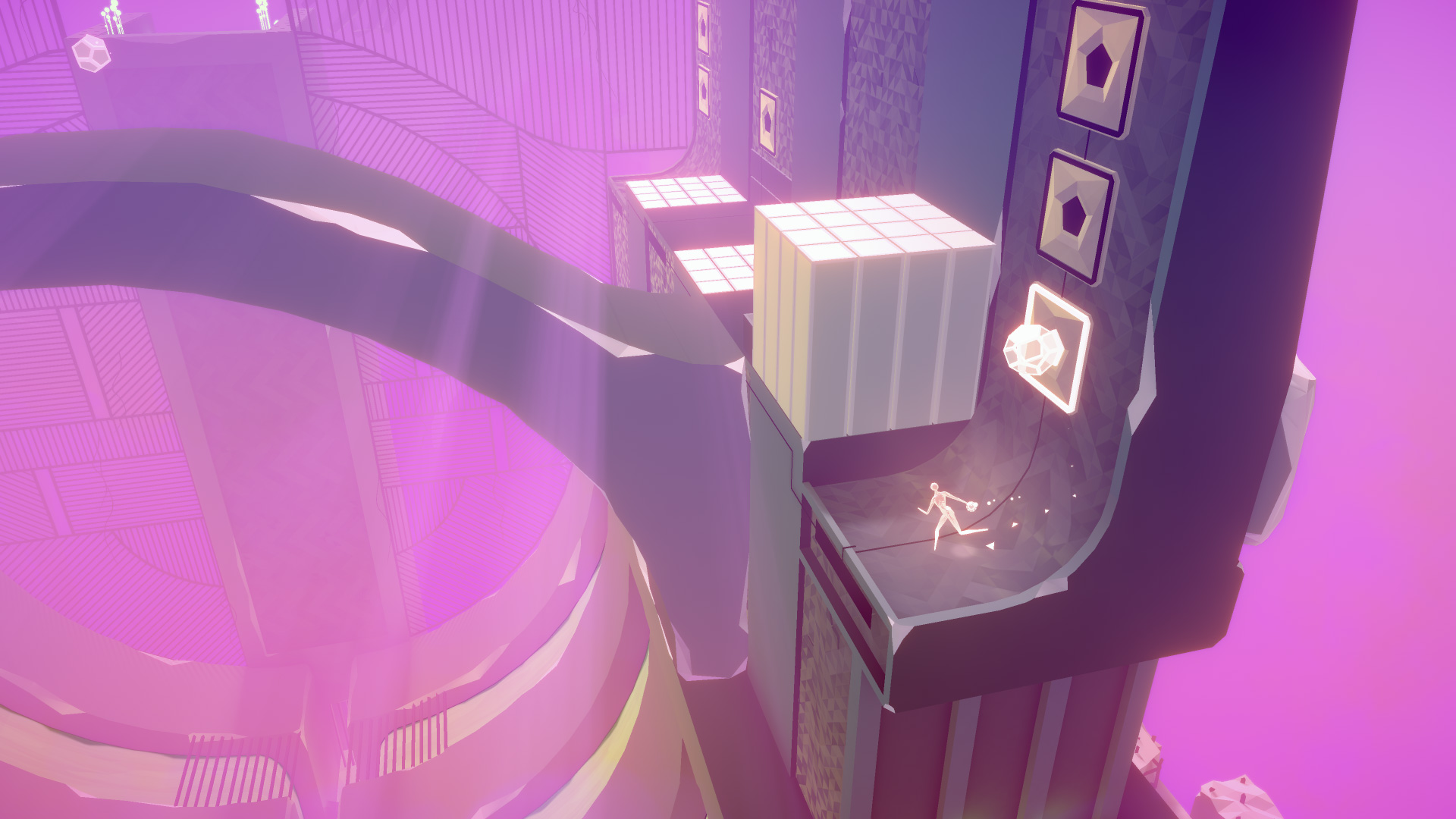

Your avatar is still subject to the laws of gravity in that they will fall if they stray too close to an edge, however, they can easily travel a path that is upside down or perpendicular to what appears to be the floor if the route so dictates. A platform with a defined edge will mean your character will fall to the next available platform or, if there is nothing there, they will simply disintegrate into the ether. Upon “death” you will reset back to the location where you fell to try again. In order to traverse the many complex routes of the Etherborn puzzles you will need to look out for curved edges that allow your character to change the orientation of the world.

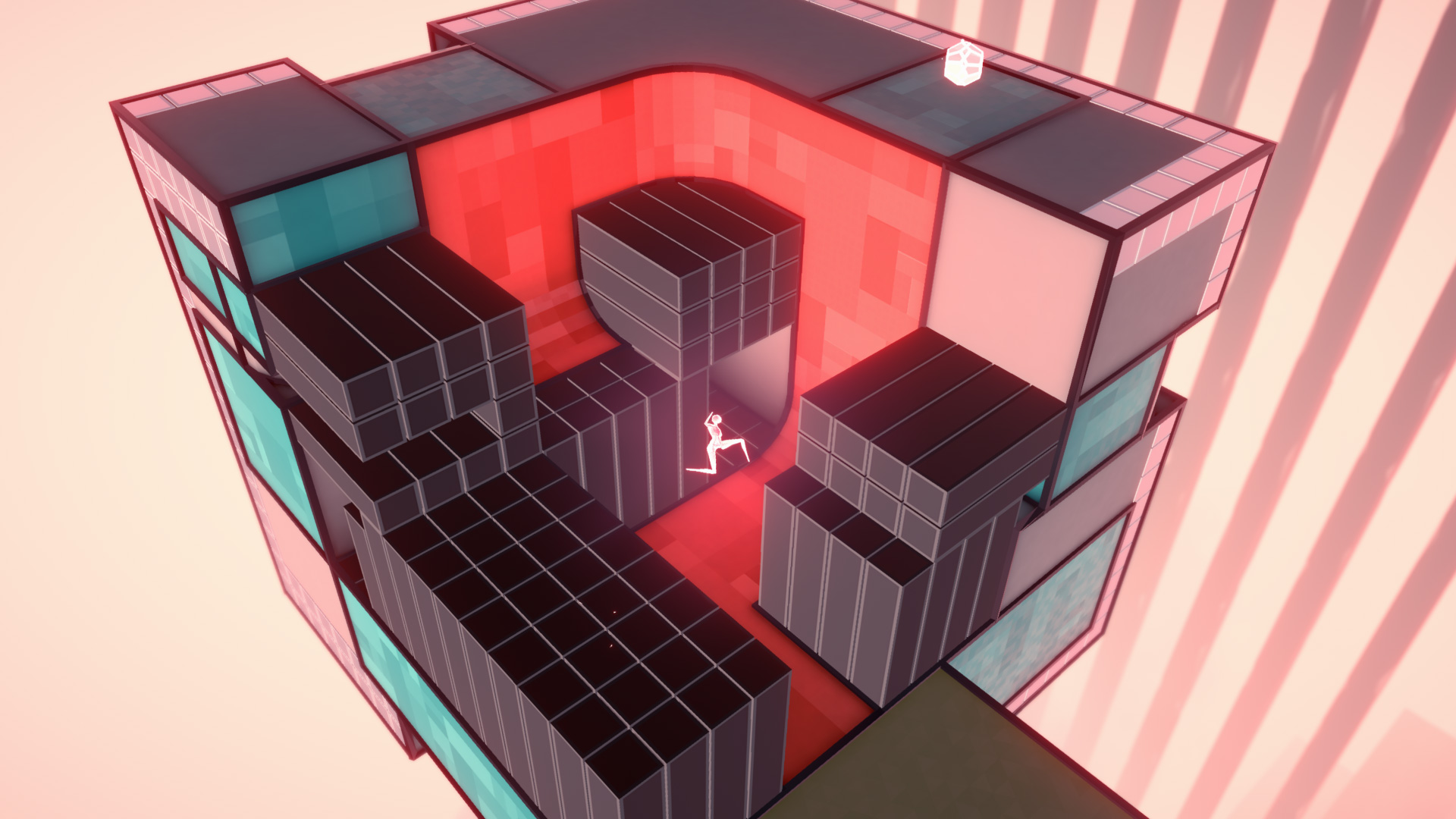

The puzzles in Etherborn are essentially the environments themselves. Spaced throughout the levels are a form of gates that are barriers to progress until you have located and brought back the orbs of light that act as keys. The challenge lies in navigating your way around the hard and curved ledges of the world to orientate yourself onto the correct path, pick up an orb and then get back to the gate with it. As levels progress these orbs are placed in increasingly more complex locations with platforms that raise up and down barring your progress and forcing you to find alternate paths as well as lethal obstacles that cause you to disintegrate and reset back to try again. There is also some light platforming elements that become more challenging as the perspective shifts and what was once right and left has become reversed or even now up and down.

Visually, Etherborn is an extremely attractive game, and the perspective shifting puzzles utilise the visuals to elegant effect with a blend of monochromatic surfaces, half destroyed structures and lush foliage. There’s also a subtle sense that each puzzle exists within a microcosm of something larger, evidenced by the fact that each level is part of a huge tree that you are climbing, however, it doesn’t quite feel that the disjointed narrative that tops and tails each puzzle does enough to actually explain what it is you are doing, or even why you are doing it. It isn’t necessary to have the answers as to why you are solving these puzzles, but the narrative structure at least hints that there is a reason for it even if that reason is obscured.

Etherborn has a strong start, but it fades towards the latter end of the game as difficulty is achieved more through a fixed camera that hinders much of your ability to accurately trace the correct path and a mechanic that can see you opening gates out of sequence. In one of the worlds there is a puzzle where only a section of the map is available in the beginning, to proceed you are required to open a gates that will bring another sections of the map to interlock into your starting area. The issue with this particular puzzle is that you can bring the different sections of the map into play in the incorrect order. The fixed camera combined with the already carefully detailed rules on how to solve the environmental challenges can, and did, mean that I spent upwards of an hour on one puzzle trying and failing to work out how to orientate myself onto the area I needed to obtain another light orb.

It was only after I backtracked right back to the beginning and through a process of trial and error realised that there was a very specific order for bringing the other parts of the world into play, and if you did one of them out of sequence it completely blocked your ability to access a gate required to bring in another section of the map. The frustrating thing about this particular section was that at no other point throughout the course of the other puzzles I had solved was it evident that this could be a possibility. It felt like a failure to adequately communicate the solution by the game itself as there hadn’t been a bridging section from the established mechanic to this new one.

There is no denying that the space and perspective shifting structure of Etherborn is a fantastic method of creating puzzles. The increasing complexity of the structures really mess with your spatial reasoning, forcing you to look at the environment in different ways, however, as you progress through the five worlds it becomes more and more evident towards the end that the trick of shifting perspective is all Etherborn has to offer. Difficulty is achieved with what seems artificial means: a fixed camera and the possibility of doing things out of sequence, even reusing orbs. This sense of artificial difficulty is only evident in the latter half of the puzzles, and non more so in the New Game plus that becomes available after you have beaten the game once. In New Game plus you run through the same environments, except this time the orbs are located in what is described as harder to reach places, which translates to one of the early puzzles as hidden in a bush! I wanted to like Etherborn, and in may ways I do, however, it feels like a game that runs out of ideas fairly early on.