Sym Review

Editor’s note: If you feel worried you may be suffering from anxiety, please don’t do so in silence. Click here to visit the NHS page dedicated to it.

Sym has pretensions of becoming something much more than it actually is.

It’s a dark, brooding, horror-tinged platformer with plenty of thematic subtext, and is a solid effort by a developer that clearly has aspirations of tackling a difficult subject matter through the medium of games.

That subject matter is social anxiety – and the various psychological fallout associated with the condition – and though there are moments in which you see the platforming gameplay and this theme begin to connect into a cohesive whole, Sym never manages to fully entwine the two in a satisfactory manner.

Couple that with an absence of the general kind of polish you find in the better indie platform games out there, and you’re left with an admirable (if flawed) examination of the human condition, that’s tacked on to a forgettable platformer, with some social sharing elements.

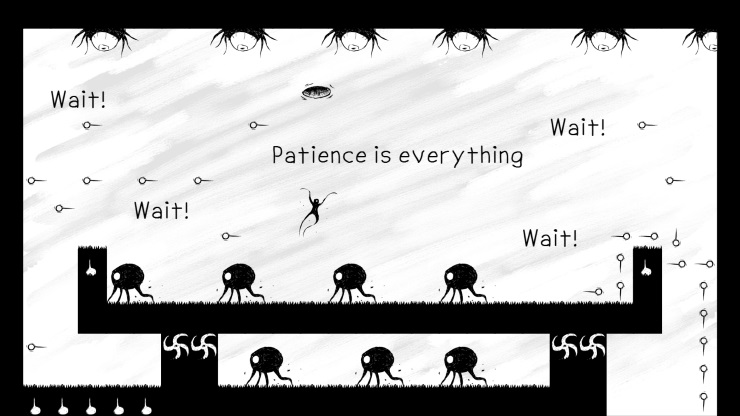

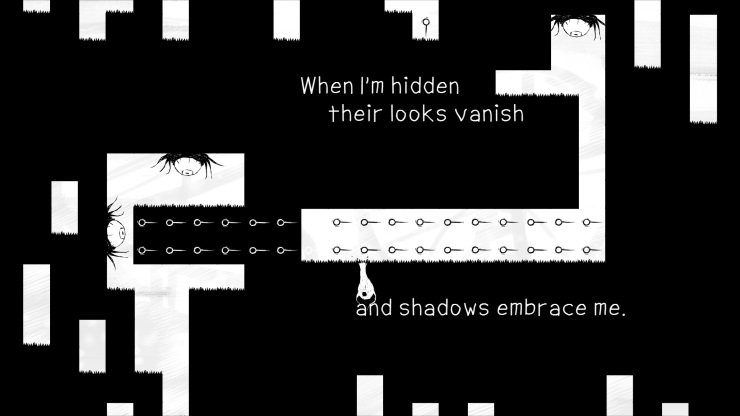

Sym’s art is low rent, perhaps deliberately so. The game opens with a cutscene that looks like its components were knocked together in a pirated version of Photoshop Elements, but its composition, conversely, is really quite striking and shows definite talent from the artist involved. The world of Sym is black and white… perhaps the black ink in the white pages of an angsty teenage sketchbook? There’s a frustration to the aesthetic, a deep desire to express loneliness and isolation, albeit without the tools to satisfactorily do so.

During play this sketchbook theory gains more weight. Our protagonist, Josh, is a teenage boy traversing sketchy worlds of his own creation, which he’s made to desperately try and avoid dealing with the everyday terror that is social anxiety. His movement animation splatters and splutters into life as you press an arrow key, and ceases the moment you lift your finger from it, running and jumping stiffly from platform to platform. It’s a binary experience: you are running or you are not running, and there’s little finesse to be found in this herky-jerky movement.

But in some ways that’s fine, because the 44 levels that comprise the single player story lack analogue nuance too, being as they are constructed out of block assets placed together by the developer, much like LEGO, to create something more than the sum of its parts.

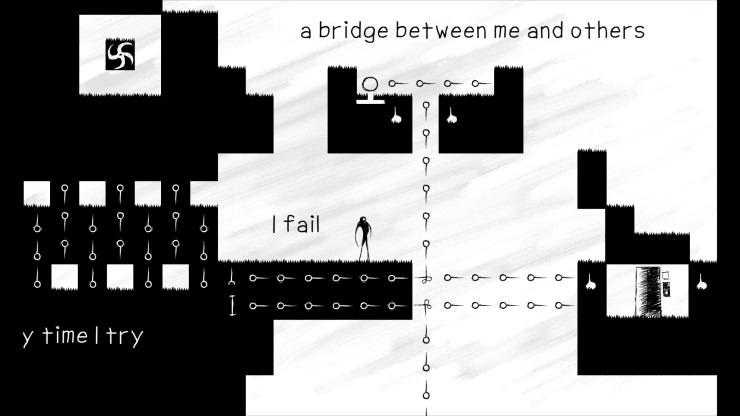

You drop from a portal onto the stage, and must then get to a door to exit. Much like similar puzzle platformer Shift, you can flip between the black and white worlds, sinking through the floor and back up again to approach a stage from a fresh perspective. It’s an effective and often mind-bogglingly complex gameplay mechanic, especially in later stages where things get really tricky and time is of the essence. For example, walls might suddenly become chasms in the floor, or insurmountable obstacles might be the set of stairs to the exit you’re looking for.

Depending on which “world” you’re in, you’ll face different foes. Large insect-like creatures wander about stages to gobble you up, sharp blades will kill you upon contact, and even the plant life thinks you’re an easy meal. The former two adversaries are put to good use, with the creatures especially providing an unpredictable element. But the snapping plants feel like they’re only included to be cruel to the player. There were multiple times where I’d get to the end of a stage only to be chomped by a plant right by the door, and then I’d have to restart the whole level again. Maybe that’s a clever metaphor for the kind of agoraphobia that can develop from social anxiety, but in terms of gameplay it’s frustrating when they’re used like this, especially considering the high challenge most levels pose.

But this difficulty isn’t from the platforming itself. As noted, there isn’t a smoothness to the world navigation that would allow for a Super Meat Boy level of gameplay challenge. Instead it’s the fact that each area you’re plonked into is a little puzzle to unravel through experimentation, logic, and blind luck.

Special blocks will begin inverting their colour when triggered by a shift of polarity or by stepping on a switch, and knowing how the world will react to your movements becomes key to success. Each stage is quick to get through if you know what you’re doing, but most will take a while to figure out. Admittedly it would take less time if you could pan around each level and survey what lay ahead, but the sense of claustrophobia and anxiousness concerning the next leap you’re about to make wouldn’t be quite so palpable, I suppose.

But this is a rare example of where the theme marries up with the gameplay. For the most part the social anxiety element is only explored through vague or cryptic sentences written on the walls of each stage. It’s an almost superficial treatment of the subject, one where you see eyes watching you; but never feel as if you’re being scrutinized, where the soundtrack promises seclusion and chaos; but never stops droning on and loops the same tunes for hours on end. Sym is a game that tells you it’s about a terrible phobia, but doesn’t quite make good on that promise.

Actually there is another exception, and I think it might be the closest the game gets to brilliance. Sym comes with a level editor so you can construct your own stages, upload them to a public server, and have strangers play your levels. It has the potential to be a kind of group therapy, a safe space to make worlds for each other, instead of for ourselves, connecting with others rather than remaining solitary.

Making a level is wonderfully easy, with just a few clicks of the mouse allowing for pretty much anyone of any skill level to make their own world in minutes. But during its launch window Sym either doesn’t have a lot of stages available, or finding the good ones isn’t easy. The saving and uploading process is also a bit more fiddly than it needs to be.

So Sym might not be perfect then, but it’s a totally okay video game, and the fact that it’s ambitious gets it some brownie points too. This isn’t the new Braid, it’s not the next Limbo, but if you like puzzle platformers, and you’re prepared to be a little forgiving, then it might just tide you over until the next must-have atmospheric adventure is upon us.