RePlayed: Left 4 Dead 2

There are certain things I simply don’t question. I don’t ask my wife why it’s so important that I put the toilet seat down. I don’t question why you shouldn’t eat silica gel (although I really, really want to). And I don’t question the popularity of zombies. The reasons that I don’t question these things and many others are simple: I like a quiet life at home, I’m not sure you should eat anything with “gel” in the name, and I really like zombies.

Skipping the first two for now (unless you want me to go deeper into the toilet seat / silica gel discussion, in which case we should probably talk in private), and focusing on the zombies instead, you’d be forgiven for wondering why I use the word “like”. The attraction of zombies is simple. Now before that leads me down any kind of necrophillia-oriented rabbit hole, what I mean is that there are lots of reasons that a frightening percentage of people look forward to a zombie apocalypse in roughly the same way as they look forward to a new verruca. It’ll be unpleasant, sure, but more of an irritant than anything actually life-threatening. Zombies are easy, you see. People in films get bitten by zombies when they’re looking the other way, or standing in front of an open window, or are stupid enough to trip over. And I’m talking mindless, bitey zombies here, not those super-violent rage-infected fuckers that Danny Boyle likes. Let’s be dead honest here: no one is surviving them, are they?

I’m talking the more traditional zombies. The ones who either shamble, or stand swaying in doorways, then shriek when they see you and run directly at you with as much idea of what to do when they catch you as a dog chasing a runaway piano. The easy zombies. The video game zombies. Now those three words held together in a single matrimonial sentence will immediately bring to mind particular titles, such as Resident Evil and Day Z, but even those zombies are too smart for my taste. I want zombies that are so damn stupid, they only kill you because there are so many of them. Like in World War Z if World War Z were an actual zombie film. I’m talking about the zombies – sorry, the infected – in Valve’s Left 4 Dead games.

SURVIVAL OF THE THICKEST

I’m aware that there are two L4D games, but because I’m that type of heathen that often thinks sequels are way better than the originals and because clever DLCing (yes, I’d like that to be a verb, please) on Valve’s behalf pretty much merged the two games anyway, I’m focused on Left 4 Dead 2 in this edition of RePlayed. For me, it’s the ultimate zombie fantasy game, but I appreciate that that statement will need some clarification before the internet implodes.

There is a major difference in my eyes between a zombie game and a survival simulation. Slapping L4D2 and, say, State of Decay into the same category is like saying Borderlands 2 is practically the same as Spec Ops: The Line. I have a lot of time for survival sims in all their forms, but sometimes when I power up a console all I’m hankering after is the cathartic thrill of blowing the ever-living shit out of something, and very few games can scratch that particularly violent itch better than Left 4 Dead 2. It’s the perfect game for relieving the stress of the day, particularly if you leave the difficulty setting on normal and opt to go hell for leather with the chainsaw for a few hours. I used to stick Left 4 Dead 2 on when I had ten minutes to spare, or when I was feeling shittier than normal for whatever reason. It isn’t the most immersive game, and it certainly isn’t the deepest, but it is unbelievably playable – and quite often, that’s the only thing that matters.

The unfounded furore when it was announced a scant year after its series progenitor was, frankly, laughable; proof, if ever you sought it out, that the internet as a gestalt is a whiny twat who will complain about pretty much anything. What did it really matter if all Valve did was make a series of cosmetic improvements and design tweaks when the leap in quality was so high? The original had some great levels, no question, but the sequel outdid every single one.

ARMY OF ONE

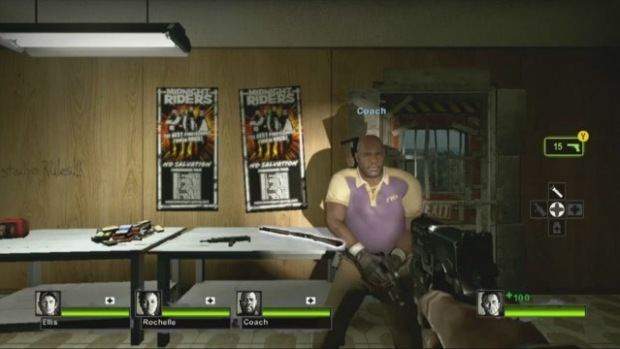

The simplicity of the premise is what makes both games so accessible. You take control of one of a group of four survivors of a deadly infection turning people into mindless, rotting cannibals. With the story mode divided into separate “campaigns”, your sole mission each time is to reach an evacuation point and get the hell out of Dodge. Each campaign is split into five parts, and any part of any campaign is accessible from the word go, meaning you can jump in anywhere you like, replaying your favourite sections over and over again, or choosing to play the game canonically or otherwise. Throughout each campaign you play alongside the other survivors, controlled either by AI or other players. By far the best way to play is with a full team of friends, as each scenario throws up countless moments that require gutsy teamwork. It’s perfectly playable with the AI, of course, but once you ramp the difficulty up past normal you’re going to struggle thanks to the iffy path-finding, odd target prioritisation and occasional rampant stupidity.

Left 4 Dead 2 likes to mix things up where its infected are concerned. While the first game had its fair share of “special infected”, it wasn’t long before players found ways around them. A prime tactic in Left 4 Dead was putting your back against a wall, or fighting back to back with another survivor. This worked perfectly well against specials like the Hunter, who climbs walls and leap-attacks you, or the Tank, who basically thrashes around smashing things up without much thought or reason, and it made short work of the waddling Boomer and Benolin-craving Smoker, who could be easily dispatched by two survivors working in tandem. To combat this, Valve cleverly introduced three new specials to Left 4 Dead 2: the “Jockey”, who pounces on survivors and forces them to walk away from their current position; the “Charger”, who literally charges right at you and then pummels you into the ground; and the Spitter, whose acidic saliva makes you her bitch if you stand in one spot too long. Valve balanced things out nicely by giving us melee weapons to use in a pinch, from katanas and bats to a handy chainsaw. They also invented “Boomer Bile”, the collected mucus of a Boomer that attracts every zombie in the vicinity and sends them bananas. Throwing one at a Tank is a particularly therapeutic delight.

For many, multiplayer is the meat and potatoes of the game, played in modes that casts one group of players as survivors and a second group as the infected horde, able to spawn special infected more or less at will and throw everything at the opposition. While the multiplayer is solid – now even more so thanks to the inclusion of mode-altering “Mutation Mods” – for me, the purer experience is the campaign, whether alone or with others. The genius AI Director 2.0 is a revelation, altering sections of the environment and choosing which enemies and pick-ups to hurl at you based on your performance. Play too well, and the Director ups the ante, maybe throws a Tank at you or a couple of rampaging hordes in quick succession; play badly and it might take pity on you, dropping an unexpected stash of ammo or a first aid kit.

DIRECTOR’S CUT

The AI Director makes the game unpredictable. While it’s not entirely procedurally generated, not knowing what’s coming from moment to moment keeps you glued to the game and fully engrossed, afraid to take every step into the unknown. Factor in some of the most enjoyable levels I’ve ever played in a shooter and you can see why I regard Left 4 Dead 2 so highly.

Particular highlights are Hard Rain and The Parish. In the former, you’re first tasked to fight through an overrun Midwestern town, complete with quaint garage sales and picket fences, before crossing a cane field to a sugar refinery completely infested with Witches. More terrifying than the Tank, a Witch in Left 4 Dead 2 won’t attack you unless you get too close or somehow spook her, at which point she goes bat-shit crazy. Hearing the tell-tale, eerie weeping of just one of them is frightening, let alone the cacophony in Hard Rain’s refinery.

But it’s upon leaving for the trip back that this campaign comes into its own, when the storm that has been threatening for the first few acts suddenly unleashes a deluge on the town, and you’re forced to run blindly through scalp-high sugarcane in the thundering downpour. It’s an epic moment, and when played with friends is one of the greatest levels of any shooter ever. The Parish is also fantastic, as you struggle to cross a bridge to safety – while the military are bombing it. It’s a fast, frantic scrabble for survival that tops the whole game off perfectly. It’s a toss-up between The Parish and Dark Carnival – that sees you set off the pyrotechnics at a rock concert to summon a rescue chopper – over which one is my favourite campaign behind Hard Rain.

As with all great games, especially in the horror genre, the best bits of Left 4 Dead 2’s admittedly simple story are the subtle details. Dialogue between characters divulges backstory and gives context to the carnage, while reaching every end-of-act safe house reveals a wall scrawled over with messages from survivors that include directions to evacuation zones, heartbreaking letters to family members, and no shortage of in-jokes. This tiny element alone is enough to add a heap of depth to Left 4 Dead 2, single-handedly making you feel that you’re part of a greater story, a grander unfolding. You’re not the only people left in the world, and your characters aren’t the only ones suffering and struggling to stay vital.

KILL ALL SONS OF BITCHES

Some exceptional DLC campaigns are the icing on the blood-stained, rotting cake. The Sacrifice pitches you as the original survivors from L4D1, Bill, Zoey, Louis, and Francis, and the “crescendo event” forces one of you to give your life to save the others. Canonically, this is grizzled war veteran Bill, but in practice it’s down to the group to decide. The Passing DLC then sees both groups, sans Bill, meeting up and helping each other survive an onslaught of infected. Both are, frankly, masterclasses in how to do DLC, and then by offering the first game’s entire campaign roster as downloadable content for Left 4 Dead 2, Valve showed just how much they wanted the community to remember and enjoy the first game – a stark and final response to the 40,000 naysayers who chose to boycott L4D2 after its initial announcement.

So Left 4 Dead 2 isn’t exactly smart. It’s not the biggest game (though the DLC adds considerably to the longevity), nor the most intricate, and it certainly isn’t the best-looking. But what it is is a perfect example of its own genre, a post-apocalyptic zombie blaster that doesn’t take itself too seriously. It’s not about scavenging for supplies, rescuing other survivors or shoring up defences; it’s about shooting dead things in the face until they stop trying to eat you and getting out of a shit-storm alive, over and over again, alone or with friends. Left 4 Dead 2 is the ultimate zombie game for exactly one reason: it reflects everything we love about zombies in movies and games, the blasting, the camaraderie, the one-liners and last-ditch bombast and removes the stuff that would actually be scary, like looters, starvation and, I don’t know, having your lower intestines ripped out and eaten while you watch.

Left 4 Dead 2 is as close to an actual zombie apocalypse as I ever want to put my face, and it’s also one of the most enjoyable games of the last generation. Should Valve announce a third, I’ll expect fully procedurally-generated environments and even more special infected, but all I’ll really care about is that they don’t mess with the formula by making me think. That’s the last thing I want to do during a zombie apocalypse.