Centum challenges you beyond the confines of reality | Hands-on preview

I think Centum could be one of the best horror narratives of all time. There, I said it. Bold as a statement as that may be, I’m fully behind it because I have just finished the two chapters available in the preview and I’m left in awe of what I’ve played. What started off in a prison cell with a rat trap, a table with some paper, a tin cup, and a weird cubical contraption on it, and a window looking out over a city, became a journey that took me to some existential and disturbing places, tinged with moments of sadness and regret. Hack the Publisher has got something special on its hands.

It’s hard to explain what Centum is. You’re developing a game or a program, but you don’t know it straight away. You think you’re in some weirdly religious circumstance where the gods are mad and you await your judgment from the confines of some dank, Medieval cell. It’s a point and click game where you interact with various items, all changing over time, and each run through lasts for three days. Once the three days are over, the program ends and you’re sat in front of a computer screen. There are notes for you to read on there, but the sole purpose of the program is to escape the cell.

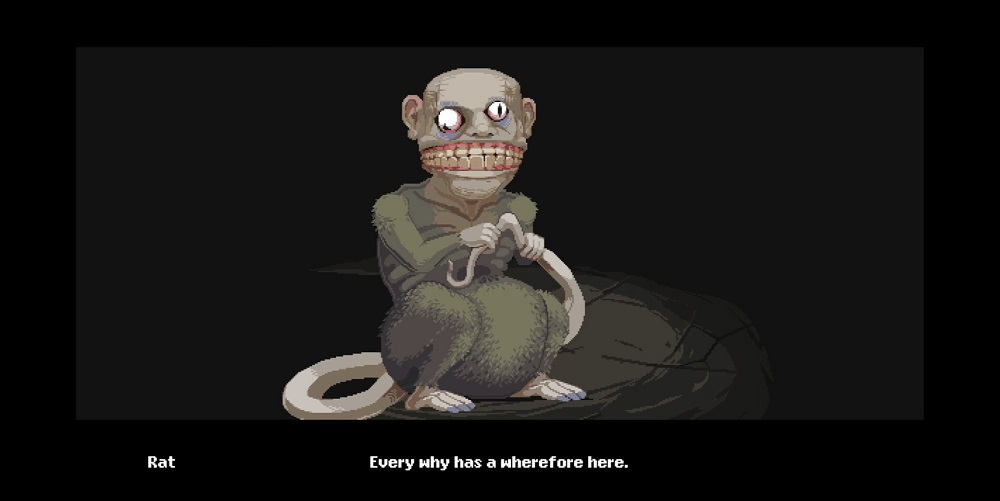

I cut my finger off in the rat trap, and from my severed finger I grew a tree that flourished in the corner of my cell, watering it with blood that filled up that tin cup on the table. I met a rat with a human head who’s nose kept pouring with snot, only to poison it and then drink the poison myself. On the third day, the city outside the window burned, and I was forced to answer questions from the AI that controlled practically everything I had to do in the preview, be it in this cell or later on in my own apartment. Yeah, suddenly Centum flips everything on its head and you end up back in reality.

Perhaps the most fucked up thing in the cell was the strange boy that came to the door on certain nights, wanting to be my friend. I had to find something to trade with him if he was ever going to let me out, and when I gave him a pen, he seemed pretty excited, finally opening the door the following morning and freeing me. From here, I answered more of his questions and started on my path to freedom, leaving the dingy cell and my finger tree behind. Centum already had me invested at this point, but things only got weirder, darker, and more intriguing.

I don’t want to give too much more away, but I ended up in my apartment. I was developing something on a deadline, there were people getting hurt as a result of my actions, and I was so alone. I would flit between reading emails and playing minigames with tanks and racing cars, and a man who kept asking me to pick one of three drinks for him. The emails started to reveal clues for future puzzles, including a deceptively smart one involving six mirrors and flickering lights reflecting from them. There was a cat with tentacles coming out of its head who kept calling me Dad, and every night my apartment started to fill with dripping blood and cracks on the walls.

The narrative became so muddled yet so clear at the same time. I was nervous and approached every new conversation with trepidation, and there were then moments that struck a chord and became rather moving, particularly one conversation involving his mother. Centum is what games should be. It is expressive art recused from boundaries or restrictive creativity. It does things games seldom do, especially now, and it reminded me of The Stanley Parable and The Beginner’s Guide, two of my absolute favourite games of all time because they dared to be different, and Centum is unlike anything I have ever played before.