An interview with Andreas Firnigl, founder of Nosebleed Interactive

Put yourself in the shoes of Andreas Firnigl. Employed by Cohort Studios (which developed Buzz! Junior and PlayStation Move game The Shoot amongst others), he was made redundant when the company folded in 2011. Within two months, he had started to call in favours, and research how to start up his own company. Thus Nosebleed Interactive was born.

Fast forward a little, and Nosebleed has a game prototype thanks to funding from what is today the UK Games Fund. At this stage, Firnigl is pitching his company’s first game to Sony. A new, unknown developer trying to sell its first game to one of the biggest companies in the world. Nervous but determined, he has a… complication to deal with.

“If I’m honest, I was really hungover,” he tells me. “All the other people were looking very casual, no one else was wearing a suit [like me], I thought ‘Oh god. I’m not only hungover, I’m also woefully overdressed.’”

Andreas was one of several developers trying to woo a group of six Sony executives. Despite his mildly marinated mental state, he found that he instantly enjoyed one advantage over his competitors. Thanks to some help from people with experience at Ubisoft Reflections, Nosebleed’s engine – built for the not-yet-dead PlayStation Vita – was “more fancy than any of the [other] samples Sony had [seen]”. Better yet, one of the executives (who would end up being Nosebleed’s producer on the game) was reluctant to give up the demo to his colleagues, uttering the immortal words “oh, just one more go.”

Needless to say, the pitch was a success, and the game released as Vita exclusive The Hungry Horde in November 2014. This proved to be the beginning of an interesting learning curve. The game included in-game stickers to collect, but this didn’t quite connect with audiences in the way that Nosebleed expected. “We thought that’s quite a casual thing that might appeal to the casual players,” says Firnigl. “But actually, all the feedback was from a core audience, proper hardcore players, who loved that collection system.”

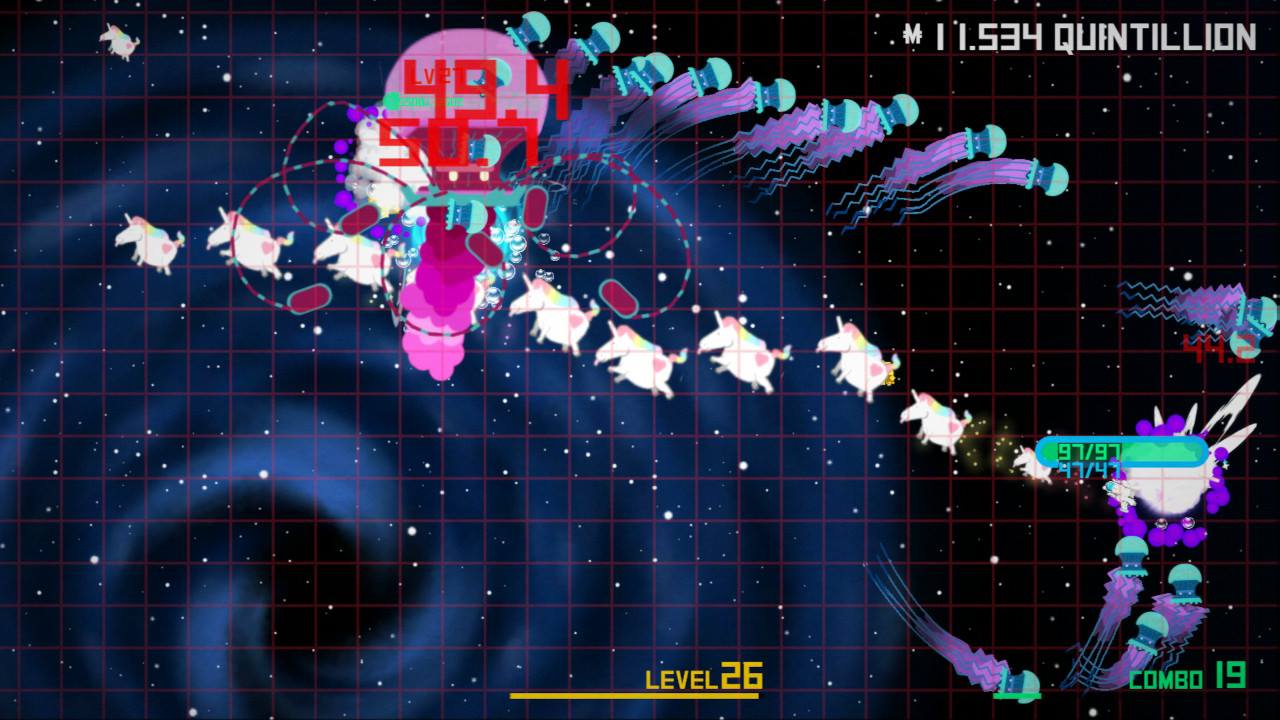

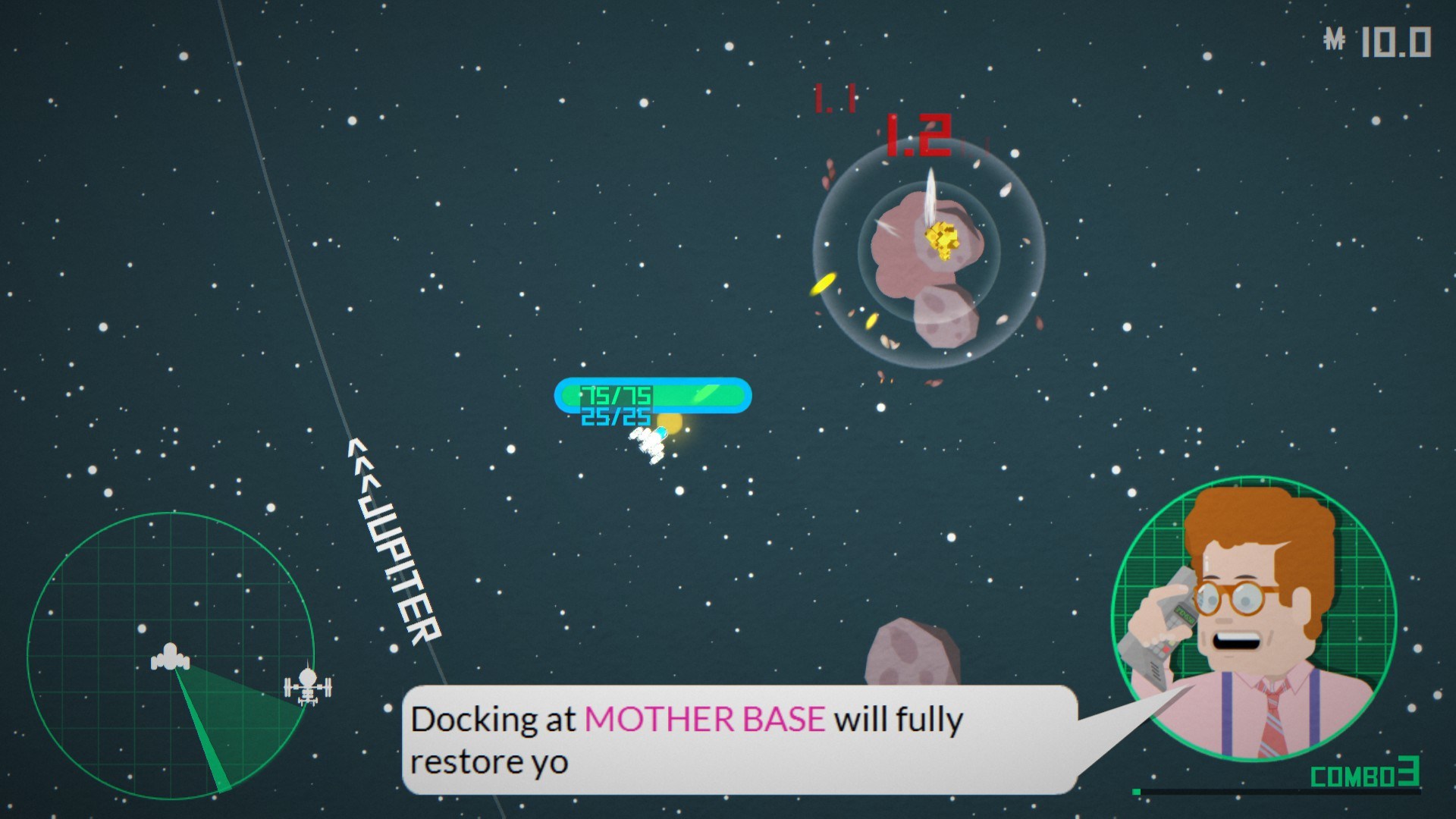

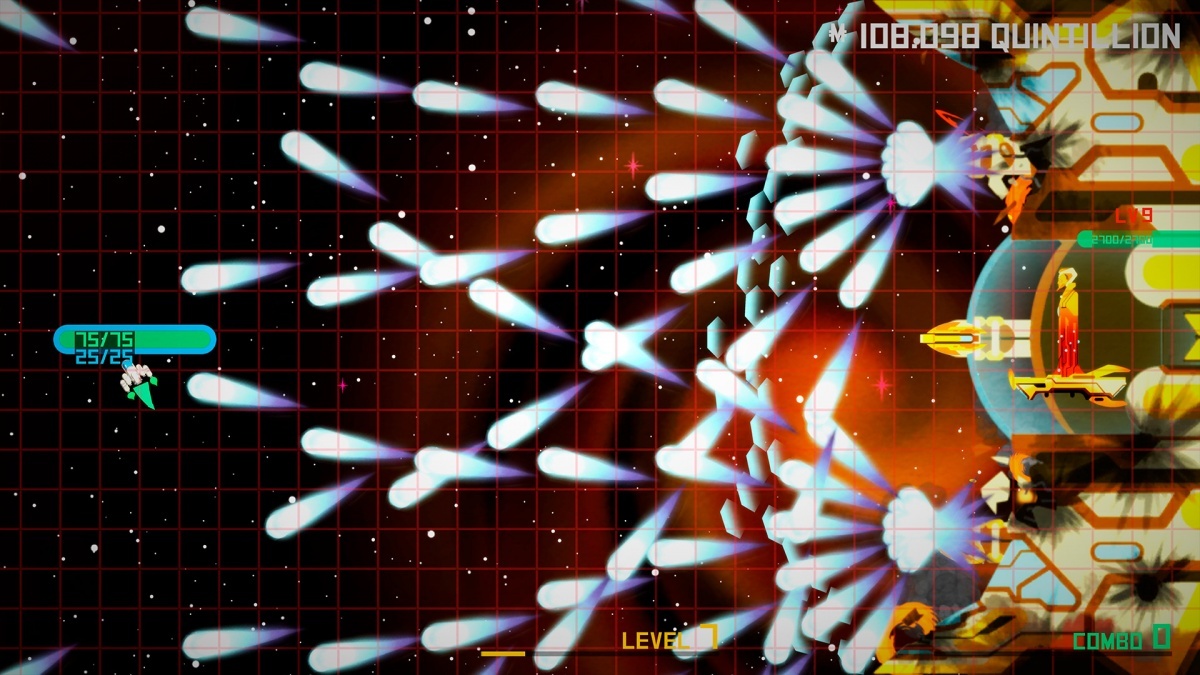

Nosebleed’s second game, Vostok Inc., is the one that the studio is best known for. “With Vostok, we kind of took a similar approach […] you think of idle games as for a casual audience, but actually, it’s the hardcore players that really engage with it. You know, the people that play World Of Warcraft that really enjoy that grind. The casual players, weirdly, are the ones who enjoy just flying around in space shooting stuff and don’t get too deep into the mechanics.”

While ‘fly and shoot’ gameplay is an important part of Vostok’s DNA, its heart pumps idle mechanics around the system. Your pot of in-game cash, “moolah”, constantly ticks up in the background. How quickly depends on how many planets you’ve visited, and what you’ve installed on said planets to make as much moolah as quickly as possible. Currency is there for the spending, of course. As well as ship upgrades, you need moolah to make moolah, as the old saying goes. This system, Firnigl believes, is effective for the way that many people consume media now.

“Watching people watching TV, nowadays everybody’s got their phone out, their tablet, and they’re doing stuff. And I include myself in that, you know […] I’ll be sitting playing something, and I’m not really concentrating on TV, because I’m playing the game; but I’m also not that engaged with the game, because I’m meant to be watching TV. We wanted to make something that is a core game; you can’t get much more core than a twin stick shooter. The Switch version is kind of the perfect version – my daughter comes in and wants to watch something on Netflix, so I’m like ‘yeah, cool, alright.’ And I’ll undock it and carry on playing. But maybe she’s watching something on TV that’s interesting, and I might put it down and watch TV, and the game carries on. We wanted to cater to the new way of playing games.”

Yet simply giving players a game that can easily be abandoned is, of course, not enough to keep them engaged. “A lot of people say ‘I love seeing the numbers tick up’ and all that kind of stuff, but actually, the people I’ve spoken to start going a little deeper. What I think actually drives play, is the fact that we give people long-term, mid-term, and short-term goals. There’s always something. With Vostok especially, we strive to always unlock something new probably every 15 minutes. I think the fact that you’ve always got something that’s just out of reach is what makes it compelling.”

The constant promise of a new reward just around the corner is an effective tactic used throughout the industry. This speaks to a Pavlovian response which can be exploited for more than just entertainment, as Nosebleed found when it embarked on a project with Newcastle University. “Stroke rehab is like physiotherapy; you have to do the same movement over and over again […] [it’s] dull.” The idea, therefore, was to make it more engaging. More fun. Gamify it.

As is so often the case in non-gaming projects requiring a motion sensor, Kinect was used to help. “Let’s say for example the doctor had said ‘right, the patient has to do this [extends arm, moves arm in a circular motion] as accurately as possible over and over again.’ The Kinect would track this movement, and score it from zero to one hundred as to how accurate you’d done it. The consultant could record themselves, say ‘this is the perfect version of this movement,’ set it out for the patient, and then the patient would have a list of moves that they’d have to do.”

Nosebleed’s job was to build this into a game. “What we built was this JRPG style thing called Sir Bramble Hatterson and the Hat of Hats. It’s this top-down map, in 3D with 2D cut-out characters. The user interaction in this was supposed to be next to nothing. These people aren’t necessarily gamers, they’re usually older, and have limited mobility, so the game plays itself almost.” The patient becomes involved when an in-game enemy appears for a fight, and they then have to replicate one of the movements set out by a consultant. The better they replicate the movement, the more damage dealt to the enemy. A real-life QTE, if you will. “It gives you a percentage score. If you do badly, say 0-10%, it says ‘almost!’ Then it’s like ‘well done!, amazing!, superb!, ‘spectacular!,’ and there’s fireworks going off and all this sort of stuff. You inflict damage, then it damages you, and you’re constantly upgrading as well. So you get more hats, and better spells, and this that and the other. So even if you die, you go back and you’re stronger, and you keep progressing.”

Sound familiar?

The feedback from the university was that patients were really engaging with, and enjoying, this gamification of their therapy. Where things got really interesting was actually before the project was complete, and the game part was still in the testing phase at Nosebleed. “When we were testing this, internally, friends coming into the studio or whatever, we had it set up so that you’d press the spacebar and it would give you a random value, because we didn’t have the Kinect stuff at the time. Press spacebar, random value, done. It’s about 15 minutes of gameplay to play the whole thing to the end, and then loop back round. Almost everyone that started it finished it. Because you’re getting told well done, you’re getting this lovely explosion of colour, all this pleasant stuff. And kind of want to see what happens next.

And it’s weird, it’s that thing of constantly being told ‘well done’. You can see where the next thing is, and you know it’s ten seconds away, ‘ooh, which enemy am I going to fight?’ or ‘I’m going to get another hat.’ It was weird psychologically that even people who knew it was just a random number, would still play it all the way through to completion.”

Nosebleed has a lot to build on, therefore, and it’s keeping all this in mind for its next game. Currently untitled and being pitched to publishers, it’s a racing game whos biggest influence is – I kid you not – PS2 RPG Dark Cloud.

“It’s got two pillars. On one side, it’s a couch multiplayer racing game, top-down. Think of something like Mashed, which is one of our most played office games. Or Micro Machines; that combat stuff. Made for you to swear at your friends, basically. For you to be like ‘Noooo!’ That’s what we’re aiming for with one half of the game. It’s set in the Vostok Inc. universe, a bit nicer looking than our last two games, because we’re not aiming at lower spec machines. All the fancy effects, and that sort of stuff. That’s the multiplayer stuff that we’ll take to shows, because it’s really easy to show, and it’s like ‘here you go, really simple controls,’ the nuance is in the fact that you’re playing against real people and they’re sitting there on the couch, and they’ve just knocked you off the track, and you’re like ‘you bastard!’”

It will still retain the Nosebleed identity which, Firnigl explains, will go much further than the inclusion of minigames. “The second pillar is what we’re billing as a CaRPG. It’s taking loot grind mechanics from something like Diablo, or Dark Cloud, or Vagrant Story, and applying them to the racing genre. Racing around feels really good inherently, in pretty much all racing games, unless they’ve broken the handling. Racing feels fun. But, outside of that, the hook, for me, is never really there. There are a few that have definitely succeeded in keeping me playing loads. But just unlocking a new car, or unlocking a new track, just doesn’t do it. I want something more.

Think of Final Fantasy VII. The second-to-second gameplay is fairly crap. You press a button, that’s it. But it’s one of my top ten games! I absolutely love it. You’re making decisions, and you’re pressing the button, but the actual interaction isn’t that much fun. But the systems behind it, the levelling up, always having that thing that’s a little bit out of reach […] that, for me, keeps me playing for hundreds of hours.”

The idea, therefore, is to thrust the racing genre deeper into grind and loot mechanics than it’s ever been, while ensuring that the core racing game remains polished and compelling. “You’ve got WipEout-style vehicles. Ish. The artwork style’s very heavily influenced by Simon Stalenhag, who’s a brilliant artist. So it’s trying to make it look real world with weird, slightly alien or slightly futuristic technology. As if it’s the 80s, but the 2080s, like we’ve colonised a bunch of planets but everybody’s still wearing high-tops.”

There’s no denying, however, that loot and idle mechanics aren’t for everybody. Nosebleed recognises this, and the plan is to have elements of the new game that can be enjoyed without the need to go through the grind and upgrade cycle. Multiplayer for example is currently being developed as completely removed from the upgrade aspect, as it’s understandably “an issue of balancing.” Multiplayer will support bots as well as human opponents and “if you’ve ever played Micro Machines or Mashed, you’ll definitely see the influence. It’s Mashed meets WipEout, basically.”

The new game still has a long way to go; but with the promise of refining all that the studio has learned about upgrade cycles, reward mechanics, and traditional gameplay, Nosebleed might just manage to reach the next level.