Character Select: Clementine

Name: Clementine

Game: The Walking Dead Season One (2012)

Species: Human

Quotes: I want my parents to come home now…

There are spoiler warnings and there are spoiler alarms. This is the latter: do not ruin this game for yourself.

Like all good horror stories, The Walking Dead taps into a primal human fear. It’s a zombie story, and like many zombie stories, it doesn’t exploit our fear of death so much as our fear that all our earthly struggles are futile. In a great many merciless zombie stories, hopeless protagonists can to do no more than prolong their hard, miserable lives. In the best zombie stories, death is not a threat in itself so much as a constant, shuffling, groaning reminder of the bleakness of the life it leaves in its wake.

The Walking Dead is a sinewy hybrid of traditional narrative, in which such stories are common, and the kind interactive storytelling normally found in games, in which more zombie stories are about triumphing over hordes of squishy adversaries than wrestling with existential angst. Its greatest strength is not only in making you feel responsible for a great number of its ghastly events, but also in making you believe that despite that, nothing you did ever made much difference.

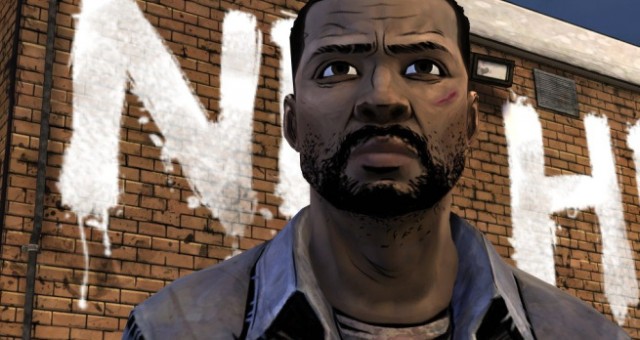

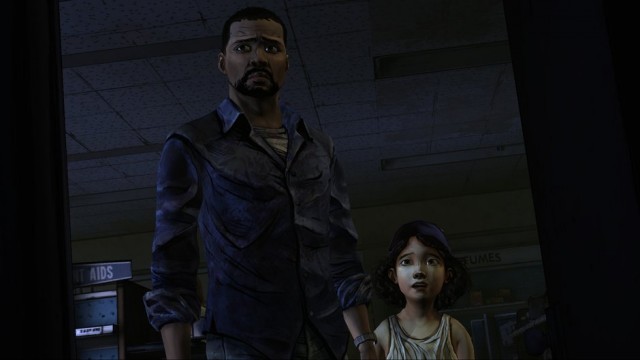

It does this mainly through Clementine, the small girl whom the protagonist, Lee, finds fending for herself in a treehouse in the early stages of the game. Immediately assuming responsibility for her, Lee (and thus the player) prioritises her well-being above all else, and the gameplay is a constant battle between the practical need to arm her with the tools she’ll need to survive and the instinctive desire to protect her innocence.

The story is helped by the fact that Clementine is so idiosyncratically lovable. After a slightly fraught design process (chronicled in “Creating Clementine”, a Game Informer article), the character emerged as unique and flawed enough for any player to believe in her and sweetly principled enough that they would want to save her no matter what the cost. Although much of the story’s power relies on the player’s desire to protect, it probably wouldn’t have provoked that desire so successfully if the child in question had been Duck, rather than Clementine. But although Clementine is brought to life with a combination of idiosyncratic design, subtle writing and nuanced voice acting, it is the position she puts the player in that makes The Walking Dead so devastating.

About half-way through the story, Lee rounds upon Chuck, a newcomer to the group, for telling Clementine that she’ll die. At first enraged that the stranger would speak to Clementine in such a way, Lee quickly realises that there’s truth in the old man’s pronouncement, and that for her to stand a chance of survival, she has to learn how to protect herself.

Thus begins one of the most quietly powerful scenes in the game, in which Lee cuts off much of her curly hair so that it’s less easy for the zombies, or “walkers”, to grab her, before teaching her how to shoot to kill. It’s up to the player whether or not Lee tells the small child to “aim for the head”. Withholding that detail might preserve some of her fragile innocence, but at the possible cost of her life later down the line.

Or at least that’s what the player is made to believe. While a single playthrough of the game preserves the illusion that the outcome is a direct result of all the player’s choices, this is not the case. In actual fact (and at this point I must firmly reiterate the spoiler warning) there is only one ending. Lee dies after having been bitten by a walker and Clementine is left to fend for herself. The last time we see her she’s out in the country, filthy and exhausted. Far in the distance, she sees two figures on top of a hill. They stop, appearing to have noticed her. She stares back, a look of terror on her face. Fade to black.

Although the player’s actions determine the way this conclusion is reached, they don’t affect what actually happens. However, their perception of the ending (especially if they only play the game through once) will depend on their actions up until that point. If they befriended loving couple Omid and Christa and told Clementine to go looking for them after Lee’s death, they might believe that the figures on the hill will look after her. But if they maintained frosty relations with other survivors and warned Clementine to be self-sufficient, they may have less faith in a happy outcome.

I say “happy”. This is still the zombie apocalypse. Even if Omid and Christa do find and take care of her, Clementine will still spend her life running from walkers and survivors driven mad by hunger and desperation. Even if the walkers are somehow destroyed, the country still lies in ruins, Clementine’s real parents are still dead and she’s still been scarred by the terrible things she has witnessed.

Which begs the question: What on earth was the point?

You may as well ask any parent. You may as well, for that matter, ask anyone who strives to make a better future for the next generation, or even themselves. No matter how much education we have, how healthy we are or how big our retirement funds, we’re still frightened bags of meat clinging to a strange little rock as it hurtles through the backwaters of an uncaring galaxy in an incomprehensible universe.

If you think about this at all, you get vertigo. If you think about it too long, you go insane. (This is aptly illustrated by Douglas Adams’ The Restaurant at the End of the Universe, in which the most terrible torture device imaginable is the Total Perspective Vortex, which destroys the minds of its victims by showing them their utter insignificance in relation to the rest of the universe.) As soon as our species grew intelligent enough to ask questions about its own existence, it has sought to protect itself from complete existential breakdown by using narrative to provide structure and meaning to a life too otherwise vast and complex to cope with.

This does not just refer to the way we use stories to rationalise things we don’t understand (some might argue that religion is a form of this), but also to the way we tend to think about our lives as stories, logical sequences of events which culminate in a coherent ending. Our faith in reassuring narrative – or the desire to escape into it – is the reason that we devour stories, be they novels, films, comic strips, games or even celebrity gossip.

In all but the most avant garde or post-modern fiction, everything happens for a reason. Things that don’t are goofs, non sequiturs, plot holes. Narrative is our mind’s first defence against an incomprehensible world because it dictates that none of our lives’ actions are wasted. Even mistakes result in a lesson learned or a curve in a character arc. Consciously or unconsciously, we apply these comforting rules to our everyday lives because if we didn’t, we’d crack.

Many video games are unwitting philosophical metaphors for life in this regard because not only do they generally ask us to do pointless things, they give us an arbitrary narrative motivation for doing so. Super Mario games ask us to use our reflexes to get a collection of red and blue pixels from one end of a two or three dimensional space to another, but rather than trust us to find that experience fulfilling in itself, they give the collection of pixels a name and a motivation, usually Princess Peach’s “cake”.

We might know such motivations are arbitrary, but gaming convention dictates that they exist, perhaps because games, with their cycles of difficulty and success, reflect the way we tend to frame our real life activities in a series of conflicts and resolutions in which strife is rewarded and hardships are overcome. This is possibly why we like to ascribe meaning to even the most banal of game mechanics. Take EDGE magazine, who, back in May, saw fit to dedicate a double-page spread to doing exactly that with Tetris’ long block:

“Tetris imitates life. You build an even, supported structure out of the raw materials of daily existence, and react to the challenges that befall it. You clear away the detritus to begin anew. Nothing in life is certain, but your hope is at some point that missing piece – that lover, that raise, that child, that job – will appear and fall into place. You can do your best to prepare for it by getting a good job or by stacking up those five square blocks in an even column on one side of the screen, but you can’t always plan for what life throws at you. The longer you live, the faster things get, with days and blocks falling quicker as you go.”

As far as basic symbolism goes, this is a fair conclusion to draw, but it unwittingly exhibits one of the adult gamer’s greatest neuroses: that gaming is pointless. The article, which can be read online, seems to reassure the reader (and perhaps also the writer) that their time spent playing Tetris wasn’t wasted, but in fact spent immersed in a piece of interactive performance art.

This lust for reassurance that time spent gaming is time well spent is left frustrated by The Walking Dead. We are not only denied the happy resolution for Clementine that we’ve worked so hard for, but we’re also denied closure in a narrative medium that almost always provides it. Since video game mechanics generally involve overcoming an obstacle or destroying an enemy, their stories tend to end conclusively as well. Further to this, they demand so much of our time that we tend to demand an absolution when they finally end. Even the cruellest ones (the Silent Hill series springs to mind here) either provide players with a defiantly dark ending or the chance to play the game again to get a better one.

This is why the ending of The Walking Dead is so shattering; besides the inherent tragedy of a small child adrift in a hostile world, it refuses to let the player, who’s spent so long trying to save her, know whether or not their efforts have been in vain. Unlike most other games in which the difficulties you overcome result in an evil being destroyed or an ending being reached, The Walking Dead just stops. How have the things you’ve taught or shown Clementine shaped her? Have they left her any more able to fend for herself?

Maybe, maybe not. All they can do is trust that you did the right thing, just as they do with real-life children. The powerful feeling they have at the end of the game – hope, fear, or a mixture of the two – is a direct consequence of their own actions not, crucially, a consequence of anything the game has game has shown or told them. The player forms their interpretation of the final scene as they form their perception of their real-life actions. Could they have behaved differently? Better? Would anything have changed as a consequence?

Ultimately, as we all know, these questions are useless. They’re useless in our own lives – you can learn and move on, but you can’t alter the past – and they’re certainly useless in the context of The Walking Dead, in which nothing you do can change whatever unknown fate befalls Clementine. So what, then, was the point in this game without an ending, in which you can never win? You may as well ask that question of anything else. No-one wins life, no-one gets to the end with full health and earns themselves another turn. Neither will anyone be able to see into the future after their death and be reassured that their life’s efforts weren’t in vain.

Most of us spend an awful lot of time trying to pretend these things aren’t true. Most video games allow us to escape into world where they aren’t, where you can try again and do better, reload with extra experience, or discover hidden secrets that will improve the outcome. In contrast, The Walking Dead never gives its players any respite, meaning that at the end, all the player takes away is the experience itself.

That experience, of course, is bleakly focussed. In a gaming sense, they player cannot get better at it or go off in search of collectibles. In a narrative sense, all padding is stripped away to make the player painfully aware of life’s bare bones: Survival and (perhaps) love. With nothing to distract them from these fundamental things, they are forced to choose between contemplating them at their peril, perhaps losing themselves in a void without answers, or simply carrying on: Finding food, killing walkers, keeping Clementine safe. In the end, the choice is obvious. The Walking Dead, like life itself, has to be its own reward.