Character Select: Katherine Marlowe

Name: Katherine Marlowe

Game: Uncharted 3: Drake’s Deception (2011)

Species: Human

In her own words: “I suspect I know you better than anyone, Mr Drake.”

WARNING: It was impossible to write this article without including enormous, ending-ruining spoilers for Uncharted 3, and thus the entire Uncharted series. Therefore, if you haven’t played the games: 1) reassess your life and your priorities, 2) go and play the games, 3) return to GodisaGeek a better person, 4) read this article.

As a column about noteworthy examples of character design in video games, it was inevitable that Character Select would eventually address the Uncharted series. The only question was which character would be caught under its Sauron-like gaze? The Uncharted games are famed for their heartfelt, believable characters, and just about any member of the cast would provide more than enough material for an article.

The obvious candidates are twinkly-eyed hero Nate, relatable love interest Elena, loveable father-figure Sully and dry-witted femme fatale Chloe. However, despite being incredibly well-written and acted, none of them are the subject of this week’s Character Select. That’s not because I couldn’t pick a favourite (Nate, obviously. No, wait, Sully. Actually, Elena. Or Chloe), but because I had such ease describing them as archetypes just now. Though they have more depth and humour than almost every other hero, love interest, father-figure and femme fatale out there (in any medium, I hasten to add), the fact that there are so many other heroes, love interests, father-figures and femme fatales to compare them to means that they would each make for a slightly less interesting article than one other character.

Specifically, Katherine Marlowe, villain of Uncharted 3 and whose novel approach to antagonism sets her apart from (if not necessarily above) the vast majority of video game antagonists. Marlowe is a member of an ancient British secret order with its roots in the court of Queen Elizabeth I. The plot of Uncharted 3 is concerned with her quest to discover the fabled Iram of the Pillars, or the “Atlantis of the Sands”, a city of unimaginable wealth hidden deep within the Rub’ al Khali desert, and which puts her in direct competition with Nate.

Unlike the antagonists of previous games, this isn’t just because they both happen to be after the same thing, but also because she has a personal grudge against our hero. The grudge has its roots in an incident twenty years earlier, when a young Nate snuck into the Sir Francis Drake museum in Cartegena, Columbia, and stole a ring once belonging to Sir Francis Drake which Marlowe considered hers; or at least hers to steal.

In the process, Nate also came between her and dashing treasure hunter Victor “Sully” Sullivan, whom she’d hired to track down the ring for her. When Marlowe, Sully, and a handful of her mercenaries find the boy by an empty glass case, the venom with which she confronts him elicits disgust from her paramour. “You’re nothing but a filthy, cast-off little beggar, you’re not fit to touch these objects,” she spits, before slapping Nate across the face. Horrified, Sully steps in to stop her hitting him again, and Nate makes a run for it, ultimately saved from certain death at the hands of a mercenary by Sully on a rooftop at the end of the chase (thus beginning the father/son, mentor/protégé relationship between the two).

Twenty years later, and Marlowe and Nate still haven’t got over their confrontation. It’s not just that they’ve been equally matched all that time (Nate still has the ring, Marlowe the golden clockwork cipher disk it unlocks) but also that they’re still plagued by what passed between them. Marlowe still seethes with the notion that the orphaned American should still wear Sir Francis’ most valuable legacy around his neck, while Nate is still haunted by her cruel words. The plot of Uncharted 3 revolves around his quest to prove that he is fit to touch the objects Marlowe told him he wasn’t, resulting in a single-minded pursuit of Sir Francis’ secret that puts himself and his loved ones in ever greater danger. When Chloe, Sully and Elena inevitably ask him what he’s trying to prove, he never answers, but the depth of his obsession becomes clear in a key moment halfway through the game.

Captured by Marlowe, drugged and forced to betray Sully during a hallucination, Nate regains consciousness opposite her in a Yemeni market. Wishing to interrogate him further, Marlowe recounts his childhood, a saga of “Dickensian” bleakness: “Mother commits suicide. Father surrenders son to the state at the age of five. Entrusted to the St. Francis Boys Home”. All very illuminating, but it’s the revelation about his name that really hits home. “I suspect I know you better than anyone, Mr. Drake,” she purrs. “Of course, that’s not your real name, is it? But we won’t dwell on that…”

Suddenly, the rug is pulled from under our feet. Throughout the series, we’ve been told that Nathan’s quest for treasure and discovery is a direct result of him being a descendent of Sir Francis Drake himself, and that he feels a sense of ownership over the secrets he strives for. Although we might, as Elena does in the first game, question the veracity of the claim due to Drake’s lack of legitimate children, it never occurs up until that point that Nate himself might be under any doubt. Thus Marlowe’s revelation that “Drake” is an assumed name completely changes our perception of the character and his motivations, suggesting not a desire for validation or wealth, but a far darker and more complex quest for identity.

It also casts a new light on the game’s subtitle, “Drake’s Deception”. Not just Francis Drake’s concealment of his discoveries from Queen Elizabeth, it seems, but also Nate’s deception of his friends, the player, and perhaps himself. “Beneath that cocky exterior, you’re still the same scared, filthy little runaway, aren’t you?”, Marlowe remarks, her words carrying far more power than the snarled insults and threats of most enemies. What else but fear would drive a man to forsake his loved ones for the sake of a brave, if false identity? Indeed, earlier suggestions in the game that Marlowe’s ancient order control their enemies through fear begins to make a lot more sense after this pivotal scene.

Nate’s battle with Marlowe then, is a battle with his own demons, his own desire to prove that he has transcended his troubled origins through intelligence and tenacity, that he is every bit as worthy to pursue historical artefacts as those with more illustrious lineages. Throughout the series he repeatedly shows himself to be more concerned with solving puzzles and overcoming challenges that lie between him and the MacGuffin than he is with the end reward. He almost always discovers secrets before his adversaries, partly because he’s the protagonist and it would be pretty boring for the player if he didn’t, and partly because he’s been compelled to educate himself in Latin, sixteenth-century Spanish and the customs of all manner of ancient civilisations.

Still, although he’s clearly fascinated by history, there’s always the sense that there’s a competitive edge to his expertise that can’t be put down to either avarice or archaeological interest. This becomes clear as the plot of Uncharted 3 begins to snowball, and the risk involved in the hunt for Sir Francis’ secrets begins to far outweigh the reward. Unlike previous games, which see Nate and friends having to fight their way through bands of mercenaries on their way to the treasure, in Uncharted 3 the bands of mercenaries come to them, and very early on in the game at that. It’s not until Sully is captured and Elena threatened that Nate finally decides it’s not worth it, but by then, of course, it’s too late.

As the likely catalyst for Nate’s self-destructive behaviour, as well as just a competitor, Marlowe is an atypical video game adversary. Nate never comes up against her in a fight, and she only becomes a real threat (to him, his friends and the world as a whole) once he’s provided her with the answers she needs to find Iram and the powerful hallucinogen it contains, something he only ends up doing because he’s so hellbent on unlocking its secrets before she does.

The Uncharted series’ Creative Director Amy Hennig explains that Marlowe “challenges [Nate] in new ways rather than overtly physical ways”. Marlowe is “a more cerebral adversary, […] more guileful and cunning than some of the people we’ve run into.” Here, Hennig alludes to the villains of the previous games, Uncharted’s mercenary leader Atoq Navarro and Uncharted 2’s far more memorable Zoran Lazarevic. As in Uncharted 3, Nate spends the first half of those games playing what he thinks is some kind of jolly “find the artefact” game, only to find out that, in solving all manner of temple puzzles, he’s actually given an evil megalomaniac the means to seize control of some kind of ancient WMD, and then has to spend the second half of the game trying to stop them.

It’s just that in Uncharted and Uncharted 2, it’s generally pretty clear what the megalomaniac in question would like to do once they get their grubby paws on the biological weapon/elixir of immortality. Marlowe’s motives are less clear, and we only have Sully’s impression after a couple of days held captive by her that were she armed with the hallucinogen that eventually emerges as her holy grail, she would represent a serious threat. Far more interesting, and indeed more important to the game, is the effect she has on Nate.

Part of this effect is his ultimate rejection of the blinkered, daredevil treasure hunting that makes the Uncharted games so much fun (one hopes there won’t be an Uncharted 4 for this reason). The final scene shows that Nate has replaced Sir Francis Drake’s ring around his neck with Elena’s wedding ring around his finger. One can forgive slightly clumsy symbolism in a story that’s meant to harken back to 1930s adventure serials, and appreciate that the story’s come full circle, that Nate, having failed to prove that he’s the equal of Sir Francis Drake, realises that he never needed to, and that true fulfilment lies in the relationships he shares with those that love him.

Consequently, the lack of a final boss fight with Marlowe has a narrative consistency with the story’s incredibly satisfying denouement, even if it does leave the gameplay of a monumental game trilogy ending on a slightly muffled note. While Nate has to defeat Navarro and Lazaravic with gunplay and fisticuffs, Marlowe quite literally sinks without trace in a cutscene near the end of Uncharted 3 as she slides into a sinkhole and is buried beneath the Rub’ al Khali desert forever.

The last time you control Nate, he’s leaping across slabs of rock to escape Iram’s collapse following a small-scale (if tricky) punch-up with Marlowe’s creepy henchman Talbot. A film wouldn’t need that final hurdle, simply having the hero escape the city would be enough, but games, especially those with such a traditional, linear “explore and conquer” structure as Uncharted 3, need this kind of final obstacle, and with Marlowe gone, Talbot must provide it.

It’s testament to the difficulty of conveying a cinematic narrative in games that the final moments of gameplay in Uncharted 3 feel slightly anticlimactic. To fight a monstrous Marlowe, perhaps under the influence of the hallucinogen, would rob her of her valuable mystery, and to defeat her with a blast from a shotgun would completely undermine everything Nate learns during the game and his arduous trek through the Rub’ al Khali. The final cutscene, a tear-jerking reunion on an airstrip, is completely satisfying, and it probably wouldn’t be had the gameplay leading up to it been more pyrotechnic. At the last moment, Uncharted 3 sacrifices gameplay for story, but it’s the right decision.

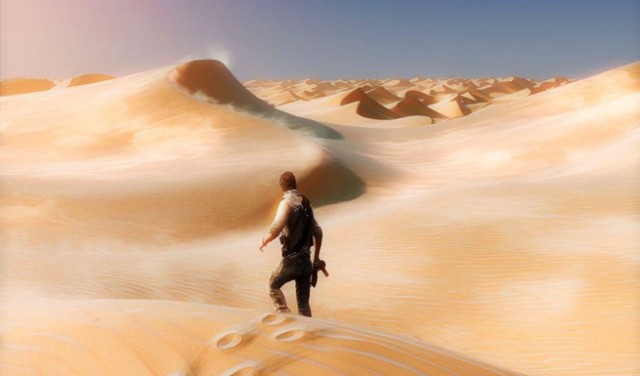

The game’s most memorable scene sees its hero stagger, broken, across the hostile wastes of the Rub’ al Khali desert, hallucinating through thirst and exhaustion. As the player edges him forward, they hear Marlowe recite a passage from T. S. Eliot’s cryptic masterpiece, “The Waste Land”:

What are the roots that clutch, what branches grow

Out of this stony rubbish? Son of man,

You cannot say, or guess, for you know only

A heap of broken images, where the sun beats,

And the dead tree gives no shelter, the cricket no relief,

And the dry stone no sound of water. Only

There is shadow under this red rock,

(Come in under the shadow of this red rock),

And I will show you something different from either

Your shadow at morning striding behind you

Or your shadow at evening rising to meet you;

I will show you fear in a handful of dust.

It is recited here not to add a veil of literary respectability to what is essentially light, if epic, entertainment, but to give that entertainment honesty and depth. “The Waste Land” has retained its power for almost a century (and will continue to do so) because its menacing inscrutability gives voice to eternal human fears of mortality and insignificance. In his desire to emulate Sir Francis and prove himself the equal of an ancient English order, Nate, like so many before him, tries to conquer these fears by proving himself significant, immortal through association with something ancient.

Of course, the “Dickensian” childhood Marlowe alludes to perhaps makes his fears of insignificance stronger, but in his rejection of the present and the real for the past and the imaginary, Nate makes mistakes that we are perhaps all guilty of in our weaker moments. As an affable everyman, a “guy in a T-shirt” (Hennig again), Nate’s relatability is what ultimately makes him such a compelling hero, but it’s Marlowe, with her smoke, mirrors and poetry, who ultimately makes us realise it.