Fable III PC Review

Developer: Lionhead Studios

Publisher: Microsoft Game Studios

Available on: PC, Xbox 360 (PC version reviewed via Games for Windows LIVE)

The Fable III series has always received a fair amount of criticism, quite often simply due to the ludicrous claims made by a certain Mr. Molyneux, but at their core, despite misgivings throughout they have always been fun and charming. Releasing a PC version of Fable III so long after the original Xbox 360 version is a tricky business, as at first glance it doesn’t really appear to be the kind of game a PC exclusive gamer would be desperately clamouring for. Can its wit and charm win out, does Fable III demand a PC gamer’s attention?

STORY: The events of Fable III take place fifty years after the hero of Fable II assumed Albion’s throne. Since the hero’s death (the character is referred to as male for simplicity’s sake despite the possibility that the player completed Fable II as a woman), his oldest child, Logan has proved himself to be a cruel tyrant of a ruler who demands extortionate taxes and executes citizens for the most minor incidences of dissent.

The player takes on the role of Logan’s younger brother or sister, who is driven to remove Logan from power after a disturbing incident at the very beginning of the game. In order to do so, the new hero must travel the land of Albion, befriending revolutionaries and gaining the support of various allies.

The missions that form the bulk of the storyline are well-written, ranging from the tried-and-tested “reunite the bickering couple” yarn to a thinly-veiled re-imagining of Dungeons and Dragons. Farmers will ask you to dress up as a chicken, and ghosts will encourage you to re-enact lost plays. The world of Albion is alive with amusing diversions and sub-plots, to the point where you’re unlikely to experience them all in a single playthrough.

Unfortunately, these missions are written with such wit and ingenuity that the banality of their execution is thrown into sharp relief. Excellent though aspects of the storytelling are, the narrative often feels like a diaphanous shroud thrown over the rickety structure of the gameplay beneath. Further to this, there are moments where you have to listen to exposition whilst being trapped in an area by (horror of horrors) invisible walls. Whilst I’m all for replacing cut-scenes with interactive sequences, being placed in a locked room and forced to listen to an NPC recite a speech does not constitute interactivity. With all this in mind, Fable III still contains just about enough interesting ideas to involve the player, especially in the latter half of the game, but whether these ideas are enough to rescue Fable III from scattergun meaninglessness is another matter altogether.

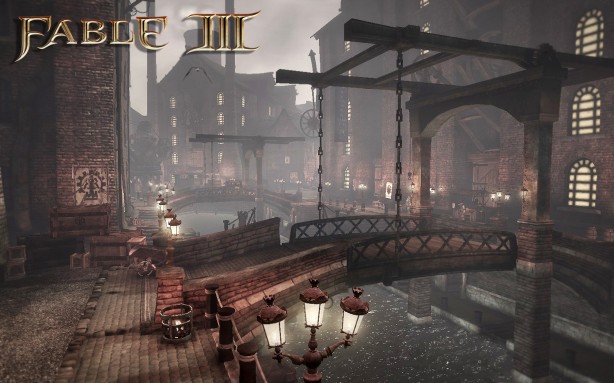

GRAPHICS: The game features a stylish aesthetic which melds Fable’s trademark fantasy with the tricorn hats and naval livery of eighteenth-century England. Logan’s tyranny takes place against a backdrop of industrialisation which parallels England’s own history despite the addition of magic and ghosts. This period isn’t much explored outside the world of historical strategy games, so it’s refreshing to see it applied to a fantasy setting. The graphics are as polished as you would hope, and the game benefits greatly from its migration to a PC. Although there’s nothing that you will have to invest in a new graphics card for, environments are well-designed and attractive.

Players who enjoyed Fable II’s character customisation options will find themselves a little disappointed by the equivalent offerings in Fable III. There aren’t nearly as many outfits or hairstyles as you would hope for, and Lionhead’s celebrated morphing mechanic is far less pronounced than in previous games. Whereas Fable, Fable II and Black and White all featured characters whose appearance changed dramatically in response to the player’s decisions, Fable III’s protagonist only begins to alter noticeably towards the end of the game.

Instead, the character’s weapons undergo small alterations depending on the type of creature it has been used to slaughter. Though some might applaud such subtlety, players accustomed to Lionhead’s more responsive morph systems might find Fable III’s conservative equivalent a bit of a let-down.

SOUND: Fable III’s ambient sound and music fare well. The music is pleasant, atmospheric and never intrusive, and the choral sections are particularly strong. Sound effects are appropriate if not especially innovative, and the mumblings of peripheral characters are always a source of amusement.

The vocal performances are less effective, mainly because the game’s integrity is eroded by its cynical casting. Despite the excellent script, almost all of Fable III’s central characters are voiced by recognisable Friday night celebrities rather than actual voice actors. It’s a matter of taste, to be sure, but there’s something a bit cheap and gimmicky about the way in which Jonathan Ross is given a fairly meaty role despite the fact that he is a television presenter rather than an actor, let alone a voice artist.

There’s nothing more likely to destroy immersion than to remind the player of the real world, and Fable III’s unfortunate reliance on its bankable cast is not only disappointing, but also shows the game’s lack of faith both in its audience and in its own material. Although it’s possible that Stephen Fry’s involvement with the project has boosted Xbox 360 sales a little since release, it’s hard not to wonder whether the resources deployed on his paycheck wouldn’t have been better spent on the gameplay.

GAMEPLAY: There are moments throughout Fable III when it seems as if the gameplay will live up to its promise and give players the rich, deep experience they no doubt purchased the action-adventure-strategy-RPG-management-simulator to experience, and had the game chosen just two or three of these elements to develop, it might have done just that.

Unfortunately, Fable III’s greatest problem is its hyperactive desire to stick its fingers in every video game pie it can reach, smearing jam all over the worktops and never once enjoying a truly satisfying meal. Every one of the game’s numerous mechanics is compromised by the others to the point where a player is likely to skate over vast swathes of the game.

Take money for example. As in previous iterations, the player can earn money by taking on menial jobs such as pie-making, which take the form of repetitive mini-games. Money can be invested in property or businesses which provide and increasing rate of return, meaning that if you so desire, you can buy large chunks of Albion and laugh mercilessly as the gold trickles into your pocket.

Despite this, for the first eight hours of Fable III, there is almost no need for money at all. Aside from an early mission which requires you to earn a nominal sum, there is nothing that the player ever needs to purchase. Health regenerates on normal difficulty, and potions are scattered and buried all over the place, so you’ll never really need to buy any fighting aids. You get given more outfits than there are available in the shops, and if you don’t get married (another completely arbitrary game mechanic that exists purely for its own sake) there’s no reason to spend your money on material goods.

So when the tide turns and the game (without wishing to give too much away) becomes all about money, it is a bit of a shock to the system. The second half of Fable III is arguably more engaging and definitely more innovative than the first, but its relevance to the first half is entirely dependent on the player’s approach up until that point.

Although fighting is frustratingly shallow (keep casting “surround” spells until everyone falls over, basically), the most disappointing aspect of the game is the lightweight levelling system. Levelling is powered by “guild seals”, an XP equivalent that is earned through all the normal means. Sadly, the options for spending guild seals render their collection meaningless. If you choose to do numerous sidequests and make several friends amongst the townspeople, you can conceivably purchase every single upgrade by the time Logan is toppled from his throne.

Matters improve once this event occurs however, and the game progresses from merely being a mashup of four genres into a mashup of a good five or six. Elements of strategy and management are integrated into the mix, and your decisions begin to impact upon Albion in a more dramatic way.

Your action-adventuring is tenuously linked to your strategizing by the “promises” which you make to your various allies in the game’s first half in order to gain their allegiance. Once you begin to wield significant power, you are given the option to keep or break them, but because you are coerced into making promises in order to progress with the game, they do not hold any narrative weight. When faced with the decision between building schools or legalising child slavery, your choice feels completely arbitrary since no thought went into your promise to build schools in the first place.

Decision-making is achieved by holding down “E” for a good three seconds, which is the length of time the game deems necessary for a player to be really certain they are doing the right thing. Whilst this makes sense in the frequent life-or-death scenarios that crop up, it gets a little tedious when you have to hold the button down for ages when all you are trying to do is open a door.

This mechanic is deployed with astonishing regularity, to the point where some lengthy missions consist of nothing else, which is almost unforgivable in a game that boasts more gameplay elements than the entire SNES back catalogue. One mission sees you re-enact a lost play, and besides walking over to the stage, there is literally nothing to do besides holding “E” for three seconds to put on a costume (which is already there, so you don’t even have to choose it) and then holding “E” for another three interminable seconds to perform. This is not only lazy on the part of the developers, but it also defeats the object of having people play a “game” in the first place. I would compare the experience to watching the special features on a DVD, but that requires pressing more buttons.

The final insult to the PC gamer is the fact that the menu screen is so counter-intuitive. If there’s one thing that the PC does really well, it’s menu navigation (oh alright, and FPS titles), so the effort you have to go to just to change your clothes is aggravating. Little has been done to upgrade the option screen (in the form of a war room) from its console origins beyond re-mapping the keys, and it is a shame that so little effort has been made to fit the task to the more capable platform.

Multiplayer is an amusing aside, enabling players to enter a friend’s version of Albion and follow them around. Friends can help with fights or annoy the locals, and it can be amusing to follow another player around their own game world. The visiting player has a fairly decent amount of control over the world they visit, including the ability to marry the player whose world they are visiting. This feature has limited scope, but it’s fun to interact with a character who is not controlled by the AI.

LONGEVITY: Despite the gameplay, Fable III’s latter half is actually intriguing enough to warrant a second run-through. There are numerous outcomes and approaches to take, and although the journey can be frustrating, it’s almost worth it just to see how an alternative scenario might play out. That the journey is not only worth taking, but taking twice despite the game’s shortcomings, is testament to its elusive potential.

VERDICT: Fable III has many grand ideas, but despite the fact that they all clamour loudly for the player’s attention, none of them are really fully developed. The game improves noticeably after the halfway point though, and patient and forgiving players will be rewarded with a more experimental experience which takes risks with genre, narrative and gameplay. The subject matter of this portion of the game is more mature and thoughtful, and the game’s evil/saintly morality compass is spun upon its axis to create an altogether more complex universe.

Fable III is an ambitious game which is not content to simply rest upon the laurels of earlier iterations. Its gameplay might not always satisfy, but it contains enough good ideas to make for an interesting whole. If you can see past the shallow role-playing elements, the occasionally frustrating fighting and the inconsistent decision system, there’s an intriguing kernel at the heart of this ambitious game.