The God is a Geek Retro Corner: Tim Schafer Retrospective

![]() Tim Schafer is one of the most well-renowned creative minds in gaming today. When news leaks that his team of developers at DoubleFine Games are working on a new title, invariably discerning gamers will get ants in their pants in anticipation. From February 8th, their new puzzle title Stacking – produced in association with THQ – became available via the PlayStation Network and Xbox LIVE Arcade and we at GodisaGeek.com want to celebrate its release.

Tim Schafer is one of the most well-renowned creative minds in gaming today. When news leaks that his team of developers at DoubleFine Games are working on a new title, invariably discerning gamers will get ants in their pants in anticipation. From February 8th, their new puzzle title Stacking – produced in association with THQ – became available via the PlayStation Network and Xbox LIVE Arcade and we at GodisaGeek.com want to celebrate its release.

The Retro Corner this month is looking back at some of Tim’s best and most influential games, both from DoubleFine Games and during his time at gaming powerhouse Lucasarts.

So without further delay, here are the five titles that shaped the career of Tim Schafer and that helped carve out his unique position on the gaming landscape:

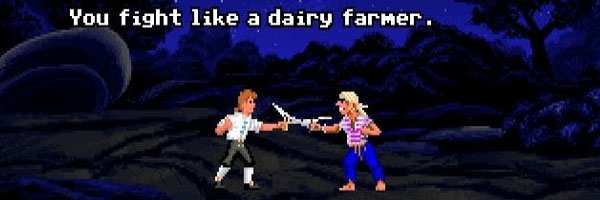

The Secret of Monkey Island / Monkey Island 2: LeChuck’s Revenge (1990/91, Lucasarts)

These were games that put Tim Schafer on the map and shaped a generation of adventure games to follow. Tim worked as co-writer, programmer and designer on the two titles at a time when PC games were big business and adventure games were always the ones at the top of the charts.

Young wannabe Pirate Guybrush Threepwood arrives on Melee Island looking for adventure. He wants to find out how to become a real Buccaneer. To do this he must pass three trials to test his skills, but in the process he falls in love and becomes involved in a fiendish plot devised by a Zombie Pirate and his crew. It is up to this untested, untrained simpleton to take on the ghostly bunch and rescue the woman he has fallen for, yet only just met. Infuse plenty of tongue in cheek humour and a few pop culture references and you have the beginnings of a series that has spawned three sequels as well as a new downloadable mini-series.

Devised and spearheaded by Ron Gilbert (who recently put together DeathSpank for EA), Tim got his first taste of the design side of gaming for these titles. Sharing the same sardonic yet off-the-wall sense of humour that has come to signal one of his games, the Monkey Island saga was the first truly funny slice of gaming the market had seen. Convention-defying for the time – the team eschewed the established save early, save often routine – whereby adventure games always had death hidden around the next corner. The first Monkey Island established a new tradition, whereby gamers weren’t punished for curiosity – rahter they were rewarded with hidden jokes and Easter Eggs. Lasting catchphrases were also key, so much so that even a villager in Fable III utters the immortal line from the games’ insult sword fighting section – “you fight like a Dairy Farmer.”

Because of this more lenient gameplay, this title was able to successfully bridge the gap between hardcore adventurers, who had been raised on text adventures and King’s Quest, and younger players who were attracted by the Pirate theme. The sense of humour was ageless and could be enjoyed by all, so the game was often played by family groups – working together to figure out the tougher puzzles. Many other adventure titles took the lead laid down by Monkey Island and it was seen as the benchmark in the genre for around a decade. ountless re-releases and the recent special edition have proven that the game still stands up strongly against its peers, and the enduring popularity of the characters has meant the series still lives on in its latest downloadable incarnation.

Day of the Tentacle (1993, Lucasarts)

The long-awaited sequel to earlier Lucasarts success story Maniac Mansion, which Tim worked on in a minor capacity as his first gig at the company, and it remains one of the most popular adventure games ever.

Jumping between 200 years in the past, the present and 200 years in the future, you play as three teenagers who have inadvertantly been split up in different times, in an attempt to stop an evil purple tentacle from taking over the world. After drinking toxic sludge, said tentacle is mutated and decides that he should take on the world – and it is in their attempt to prevent that mutation from ever happening, that a malfunctioning time machine causes chaos. To get back home, the trio must go lumber-jacking with George Washington, put hamsters through the washing machine and succeed in a pet show – for humans.

The ability to hot-swap between characters was ingenious. All three were in the same building, but years apart, so the clever part of the game was puzzles where what is done in one time period will affect the next, and so on. This added another dimension to the possible scenarios, and allowed for more complex puzzles. It also introduced the idea that certain tasks could be completewd when the player wanted to complete them. Not everything had to be done in a set order. Some tasks would hinge upon anothers’ successful resolution, but the structure of the game as a whole was less linear than other games of the time.

Working with characters from an already established series, Tim was able to flesh them out more than had been managed in the original game. This made the player connect more with the characters and them being teenagers really helped reach the target market. The progression to high-quality cartoon style graphics could afford the cast a great range of expression, and aided by it being one of Lucasarts’ first forays into fully-voiced Adventures, the game was bursting with personality. Packed with Lucas industry in-jokes, and cultural satire, the title even succeeded in getting some children more interested in American history. Did George Washington really wear a set of wind-up chattering teeth?

Full Throttle (1995, Lucasarts)

For the first title where Tim took sole creative charge, we begin to see his personality begin to really shine through. No longer placing his game into part of a series, he could really set down a marker and start his own lagacy from here.

You will play as Ben – an outlaw leader of a Biker Gang – in a world where the open road is king. Unwittingly you find yourself framed for the murder of a beloved biking icon and your quest for redemption will lead you on a violent, dangerous journey to unearth and expose a sinister plan to take over the biggest name in motorbike manufacture and to eliminate motorcyclists – for good.

In a bold move, Tim abandoned the tried and tested SCUMM advenutre game interface that had been used in all Lucasarts games for years. Simplifying the interface, he created an icon wheel of actions that would appear on items that could be interacted with. This streamlined the game somewhat, but met with some resistance as some gamers thought it made things to easy, and others were stuck in the old ways.

Foreshadowing things to come somewhat, in his later Double Fine games that moved away from his roots – and unusually for an adventure game – the team also included several action sequences in the story (mainly driving-based due to the theme of the game). They were simple, but required a lot more hand-eye coordination than simple puzzles, and often needed quick reactions. Again, this was unpopular with a lot of adventure fans. They had got used to sedentary games with little risk – now Tim had re-introduced action and consequences for mistakes.

These factors ultimately held back Full Throttle from reaching the same popularity as other Lucasarts titles, and it always seems rather short in comparison. But what does shine through is the cinematic quality of the script, set design and pacing. Short it may be in gameplay terms, but it moves along at a high tempo and really feels like a biker-flick. There are definitely a lot of things in the game that must has inspired his later title Brutal Legend, and stylistically we see a shift towards the unique Schafer traits, rather than simply following the house style.

Grim Fandango (1998, Lucasarts)

This game was Tim’s Casablanca. Aside from the fact that he drew inspiration from that very same film, numerous other film noir classics and the Mexican Day of the Dead culture – this game stands up as the best example of his creative vision realised – it is the epic story told on a grand scale, with the director’s flair on full show.

In the land of the dead, after the living pass over to the other side – but before reaching the afterlife – they must secure passage. How do they do this? Why, just ask your Grim Reaper – who doubles as a travel agent. And so begins a tragic love story where our protagonist – Reaper Manuel Calavera – loses his client Meche, after falling for her, but before he can make her transport arrangements. So begins a trek across the land to find the girl of his dreams, but also to join an covert revolution whose aim is to uncover a terrible conspiracy that is crippling those who want to get to the Ninth Underworld fair and square.

This marked the big move to 3D for adventure games. 2D was considered passe in the late 1990’s and developers felt that to keep gamers interest, they needed to switch to three dimensions. The new 3D interface may have still looked great, due to the quality of the artwork, it was clunky and has unfortunately aged quite badly. It was difficult to manouvre and interact with the keyboard – most gamers still wanted to use the mouse for control. It was a risky move and – although the game was a critical hit – sales were very bad and it is often seen as the nail in the coffin of the traditional adventure.

This was a huge shame, because the Mexican-inspired art and music was delightful. The homages paid to classic noir films was spot-on. The adventure was epic, spanning three discs and four years, with a script that veered from tragic to hilarious and back again. Characters were inventive – ranging from the suited Grim Reapers to their down-trodden Demonoid mechanics. The voice acting was also superb and featured several successful actors lending their talents.

But it was the scale of the tale that makes it stick out. The passage of time is portrayed beautifully between chapters and really adds to the film-like quality. Puzzles required some real deep-thinking to solve, but were never too outrageous. Often they could be informed by watching the source material Schafer had used for inspiration. Stuck in the Casino? Try watching Casablanca for a hint. That is really post-modern and I can’t argue with something that promotes watching such classic movies.

Despite its lack of success, it did inspire a whole wave of adventure games to move to 3D engines. None really took off and the genre entered somewhat of a hibernation for many years, but its influence on the market was undeniable – 2D adventure games just didn’t get made for a lnog time after Grim Fandango. An acquired taste due to its implementation flaws, once you have sampled its humour and style, you will no doubt be converted to the cause of La Revolucion – and you will understand why this is considered such a cult classic.

Psychonauts (2005, Double Fine)

A rollercoaster of fantastic ideas, insane characters and brilliant visions – unfortunately not always executed in the most effective way – this game is a visual and aural delight in almost every scene.

Whispering Rock Psychic Summer Camp has long been the premier destination for aspiring young psychics – but is in fact a remote US government training facility. The camp is tasked with training up psychically gifted children to become the next wave of crime-fighters – the Psychonauts. Playing as the wise-cracking Razputin “Raz” Aquato, a runaway who manages to join the camp due to his latent psychic abilities – you will stumble upon a devious plot (see a pattern here with Tim’s games?) formed by the camp Coach to extract brains from useful students to power Psychic Death Tanks, which would allow him to take over the world.

The fact that Raz is a psychic, and can enter the minds of not only his classmates, but his enemies, opens up a whole sea of potential ideas. The game treats each brain as a different world, obviously created by the imagination of the individual. For example, in the head of the Coach – former army man – his mind is a battlefield…literally! Or the mind of a sea monster, who dreams of a world where the normal population look like her, and they are terrorrised by giant humans. The level design gets even more interesting when you start to investigate the insane asylum – one stand-out level is the brain of a man who thinks he is Napoleon, which lends itself to a Risk-style board game.

These different levels allow for different gameplay types and a variety of graphic styles to be employed. Usually a game should be cohesive, but the very premise of this title means that it is alright to have a mis-match of level design and it will still sit well together, side-by-side. The one problem here is what game style can you use to tie it all together? Tim opts for a basic platforming engine, and that is perhaps its downfall. Timed jumps, awkward platforms and niggly obstacles make for a few insanely irritating sequences, that drag the game down and put the seeds of doubt in the players mind – do I really want to continue playing?!

Perhaps because of this and the fact platform games were at a low-ebb at the time of release, it led to the game flopping at retail. Another bold gaming choice from Tim, unfortunately not justified by sales. However, downloadable copies and Xbox 360 backwards-compatability helped prolong its life and it too has gained a cult following. A sequel has even been touted, but is still up in the air.

Looking back at his career, there has never been a short supply of humour, creativity or innovation in the games Tim and his teams have produced. They have been consistently funny, and the ideas and situations are always unique ones that have not been seen before in gaming. The problem we have sometimes seen in applying those ideas. Perhaps he should write films or TV – his stories and characters are so strong they could easily support a movie. It is finding a style of game capable of handling his endless imagination that has proved to be difficult. But without developers like Double Fine, gaming would be a far less interesting place. Not every game needs to be a blockbuster and make huge sales – with digital distribution so popular nowadays the opportunities for small, creative games to be possible are far greater. The risks in taking on a “unique” game are far less daunting. I hope that will mean a whole generation of developers who take a leaf out of the book of Tim. Please.

Double Fine released Stacking on the PlayStation Network on February 8th in North America and February 9th in Europe, and on Xbox LIVE on February 9th Worldwide.