Cloud Chamber is an upcoming MMO from Investigate North that puts players in the role of investigator, asking them to actively discuss and compare thoughts about all manner of materials, such as found footage style vignettes and photographs, which are ‘found’ within the digital database that is the Cloud Chamber.

In part one of our chat with Cloud Chamber’s Director, Christian Fonnesbech, we discovered the origins of Cloud Chamber’s creation, its idea, and the spark that defines how the game works. In part two Christian sheds more light on the narrative themes, the reasons behind them, and the artistic intent behind the game and, well, it all gets a bit massive…

How did you settle upon the idea to create media files as the discussion points?

How did you settle upon the idea to create media files as the discussion points?

We always had this thing, even in The Galatea Mystery we had the guy talking into a webcam, and I used to make short films – I studied film and media at University, so I made ten shorts there for no budget with borrowed equipment, standing in the rain with cables, and I even made a TV series with some of the other students for almost no money.

I was really in love with film for a long time. Well, originally I was a PC and RPG geek – I think I had ten home computers between the ZX81 and the Commodore Amiga, and I had like two meters of shelf space for advanced DnD rules and, y’know, Traveller and all that stuff – but around the end of the Amiga cycle I just fell in love with movies and I think what I fell in love with was the fact that they were so personal. That they were so emotional.

You could see that in people like Scorsese, in Lynch, in Kubrick – they were really able to make something huge, [something] that was a very personal expression of how the world worked. Games weren’t like that back then, games were more like toys. Games felt like they came out of a factory.

I know a lot of them didn’t but they weren’t, like, huge visions of how the world worked, they were just designed to amuse.

So films have been a big focus of yours for a long time?

Yeah, so, I spent seven years at University, I watched twenty movies a week, I made ten shorts, I kept hitting the books to work out why my shorts were so awful, and actually the last one I did – and this was way before Skype, it was actually in 1999 – was actually one guy talking into a ‘video phone’. It was just him talking into the camera as if it was a working video conversation and what I’ve been doing ever since then is trying to build up a fictional universe around that.

But what happened around then was that I was visiting a friend one day and he had Quake, and it totally blew me away. It was like ‘Holy Shit’. Suddenly the emotion and the technology became one and, y’know, it wasn’t Kubrick but it was huge, it was a vision of the world. It was a goth hardcore techno vision, but it’s still a vision, y’know?

[Quake] was big and I started looking around and suddenly I realised that I’d missed the 3D revolution. I’d missed Zelda: Ocarina of Time – I’d been running around in the rain with cables and I just started realising – Black and White, Half Life, these were visions of the world, these were really emotional worlds you could go into.

And bang, I fell out of love with film. That was it. I just, wanted to make games, because I just realised that – because I was also writing a paper about the history of technology at the same time, it all came together in my head – connected computers had to be the next big [narrative] medium.

So you used your experience with film and applied it to games?

I started looking around for any way to start making stories on computers, and games on computers. Ten years later I’ve done 35 of those, I have a small company that I built to make them, and then I started talking to the film institute. We’d done three of these mysteries, where the Galatea Mystery was the first one, and we got better and better at it. We really realised that we had something here. This idea of mixing found footage with some kind of social network – I mean, Facebook wasn’t even around when we made the first one – and then by giving people gameplay points we just realised that people would stay there a long time and they would get emotionally involved in a way they wouldn’t in, for example, an adventure game.

Because of the real people and the actors mixing with the other real people that you were chatting with as the gameplay, I mean, that was really powerful and it really felt like that was something that we’d found that had just been waiting for us.

Cloud Chamber is the fourth one and it’s a huge step because we made it permanent, we made it something you can explore for ten seconds, ten minutes or ten hours at a time. You can leave it for six months and come back and it’ll still be there. It’ll be different people, but you’ll still be in the same place. But what we also realised [in making these games] was that when you’re making a fiction that you’re putting people into and you’re asking them to chat and to pretend that it’s true, then it better be a fucking big fiction.

Big as in confusing? As in Broad?

Big as in confusing? As in Broad?

[It’s] because people are so intelligent, and they will so quickly reach the edge of what you’ve thought of as an author. And at that point it becomes really hard to suspend disbeliefs because you can feel the whole thing start to creak. If you put real science in there, and you integrate it really elegantly with the fiction, then it’s endless. And that’s kind of another thing we stumbled onto and that’s really what I feel is working in Cloud Chamber is that we’ve worked really hard to integrate this idea that there might be a signal, or there might be a natural phenomenon, or it might be Kathleen who’s losing her mind. You’re not really sure, but you can see the evidence, and the evidence points to real science.

So you start looking at the real science. Subatomic particles, the birth of the universe, magnetic fields, how do these things work? Could there be a signal inside subatomic particles? And since the science is real you start linking to Wikipedia articles [in discussions in Cloud Chamber], you start looking at different theories on cosmology, where the universe comes from, and suddenly you’ve got these endless, beautiful discussions about space, the universe, life, everything!

Then it pings back to the fiction – “Could that be real? Could that be what’s going on? Look at her in this scene, I think she’s lying. Let’s go back.” Getting that kind of possibility space between what’s happening with the actors and the story and what’s real in science, that actually works. It gives us a field of play that’s almost endless. And we don’t have to invent all of it, because God’s done a lot of the work for us.

Is that why you decided to settle upon creating a Science Fiction universe? Because you can use real science to bolster the narrative?

What happened was that after 35 projects the film institute says ‘so your team are interesting story tellers in this new medium, in computers, would you do one with us?’ and my first question was ‘what should it be about?’ and they say ‘that’s up to you!’

And I’m like ‘Woah! I’ve been waiting ten years for somebody to say that to me, because I haven’t had that sort of control since I was standing in the rain with cables. So my first thought was space, and then it was growing up in a family of scientists, because that’s what I did. Then I started to think – and I don’t mean for this to sound grand at all but – finally, ‘I get to play at being an artist’, which is what I always wanted.

So what I understand someone playing at being an artist does is that they get to explore something that interests them. And I thought ‘well if I’m going to spend the next couple of years – I was being optimistic – with this, what would I like to explore? And it just seemed very natural that, well, I don’t understand the universe at all.

I grew up without God. Both my parents are Biologists, and there’s not that much religion in Biology. But my Grandparents were extremely religious, so I sort of grew up and I could see that they had something I didn’t have. And I kind of wish I had it, but when you grow up in a very rational family where that kind of thing is just considered silly, then you can’t pretend to be Religious. I just didn’t have those things in me.

So the project actually became very much about ‘are we alone? What are the chances that we’re alone? What’s out there? I don’t even know. Sure I know there’s Jupiter and I know there’s the Sun and so on, but, what’s beyond that?’ It’s like, you watch Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, right, and it’s all very precise until it gets to Jupiter and then it’s just weird colours. That’s the way we’ve seen the world for about 100 years, right? It’s been ‘here’s the solar system, we kinda get that, but beyond that? Err, it’s just freaky.’

So I really wanted to go beyond that and since I’d realised that I was good at talking to Scientists I basically spent two years reading books and talking to Astrophysicists while I was making Cloud Chamber. I’ve got a lot of contacts in Denmark – advantage of living in a small country.

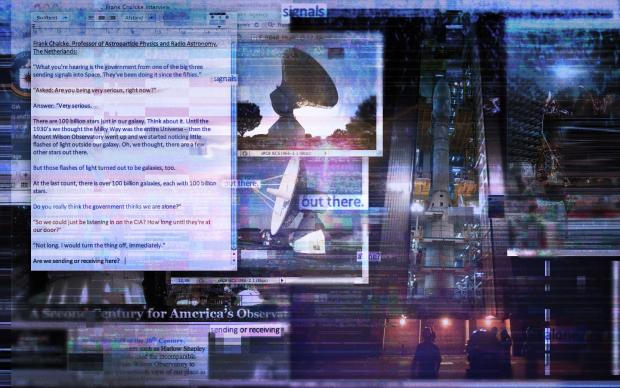

The turning points for me was when I realised that until 80 years ago, we thought the Milky Way was the entire universe. That’s 1930. But there’s 200 billion stars in the Galaxy, 200 billion just in the Milky Way, so it’s almost incomprehensibly huge already. And then in the thirties the Mount Wilson Observatory went up in California and we started seeing that there were a few flashes of light outside the Milky Way so we though, ok, there’s a few stars that got away. And then they sort of did a focus rack on the telescope and realised that oh, those are galaxies too. Oh shit.

So, last count, there’s 100 billion galaxies. Each galaxy has 100 to 200 billion stars. Seriously. This is real. This is crazy. Absolutely crazy. And the thing is, we’re still kind of stuck in this human centric vision, right? Maybe we need it to stay sane, I dunno. We still kind of think ‘Ok, there are a few other things out there, but this is where it’s at’. But we’re so insanely small that it’s just ridiculous, and the whole idea of us being alone, to me, just seems laughable.

I mean, just recently, just a month ago, it came up that there’s 40 billion Earth-like planets in the Milky Way alone. 40 billion planets are in the Goldilocks zone, which means they’re so close to the sun that the water is warm enough but has not evaporated, but they’re not so far away that it has frozen. And that’s 40 billion in our galaxy alone. We can’t talk to them because they’re, y’know, too far away, but what are the chances that nothing is living on any of them? Ok, even if there isn’t, we’ve got another 100 billion galaxies out there. And that’s the journey Cloud Chamber became about.

I wanted an emotional feeling for the universe. Like you have for your City, you have an emotional relationship for different parts of your city, and we kind of have that with the solar system. But the idea is that when you finish Cloud Chamber you will have an emotional relationship with the universe. That’s the idea.

As you move through Cloud Chamber you basically move from the smallest subatomic particles, out into the solar system, out to the Helios Sphere, into the galaxy, beyond the galaxy to all the other galaxies, right out to the edge of the universe and back to the birth of the universe. What we managed to find was a very very logical track that kept it all together, and that’s what this signal is about.

It means as you explore more and more theories about what this signal is, you’re basically chewing through stuff about the universe that goes further and further out. And I can say that that really worked because I can see it on the people that beta tested it that the discussion moves out, out, out, out, and that’s hugely satisfying to watch. That was the artistic goal of getting the science and the fiction to work together, to get people discussing that.

Huge Stuff…

Yea, and that’s Kubrick’s fault. Maybe it’s just Quake meets 2001, maybe that’s what it is. Well obviously the shooter part is gone so maybe it’s Zork meets 2001, I dunno.

I did end up with a sort of ‘can I find a rational, scientific explanation for God’, and I think it’s in there. Honestly, I do.

Part three of God is a Geek’s interview with Cloud Chamber’s Christian Fonnesbech will focus on creating a video game with people that don’t particularly like video games, and just how many sheets of A4 paper can one player fill with theories about the game?