Opinion: Storytelling Should Be What This Generation Is Remembered For

The passing console cycle has brought so much to gaming that it’s hard to pinpoint one particular innovation it should be remembered for.

Motion Control arrived and brought gaming to new and unexpected audiences, Activision’s Call of Duty series became an entertainment juggernaut, online gaming replaced split-screen gaming, and games consoles became more than just things you played games on.

With better visuals, larger audiences and bigger budgets, the sense of scale in games escalated dramatically. Indie games also thrived with the boom of Xbox LIVE Arcade, PSN and Steam giving a platform to many of the generation’s most unique titles.

Perhaps best of all, however, gaming began to fully-realise its potential as a story-telling medium. Great stories have always been told in games, but only in recent years have games explored what they can offer that other mediums simply cannot.

What games can offer storytelling is the same as what they can offer you and I over movies or books – true interactivity. Only in games can you become a leading man or woman and have a say in their story.

From Chrono Trigger to The Last Of Us, there have always been great stories in gaming told in the traditional linear way, but in the last eight or so years there has been a boom in interactive storytelling.

The biggest and most successful example would be Bioware’s Mass Effect series. What gripped so many was the ability to forge a leading character of your own. Your Sheppard could be gay or straight, male or female, good or evil – and the characters you shared that universe with would react appropriately to your actions.

It wasn’t a flawless execution of that idea but Mass Effect brought it to the attentions of millions and is an idea well worth pursuing in further games, even if the third instalment left a bitter after-taste for some.

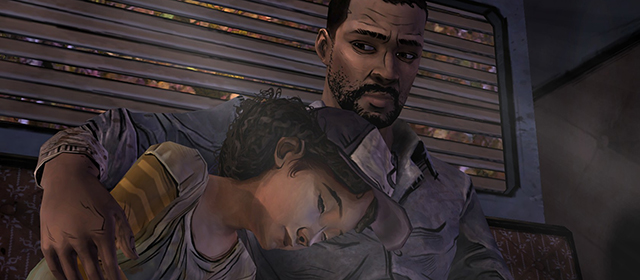

Telltale’s The Walking Dead game stripped back the action that sometimes weighed the Mass Effect trilogy down and made one of gaming’s few genuine dramas. There was still shooting (it is a zombie game after all), but at the forefront there was the characters and their relationships.

With a timer on all your decisions – from simple dialogue options to choosing whether to lop off someone’s infected limb – the game wanted to feed on your instincts and reveal what you might actually do in these situations. It often provokes regret; even guilt, with the biggest decisions able to haunt you throughout your play-through.

Of course The Walking Dead had numerous technical issues, but what everyone recognised was Telltale’s ambitions and near flawless execution of them from a storytelling perspective. The fact many overlooked the occasional glitch or bug in favour of what the game triggered in them emotionally goes to show just how successful Telltale were.

Some levelled criticism at both examples because the endings didn’t differentiate due to your choices in any major way, but that misses the point. What both Mass Effect and The Walking Dead did was allow players to tailor their journey to those endings, and it’s in the journey that most enjoyment is to be had.

So we have examples of classically linear storytelling and examples of more tailored experiences, but there’s a third example in between.

Whereas classic linear games enforce a sort-of pace (as much as you can in a game) open world settings can provide the opportunity and tools for a tailored experience even if there’s little input in the actual story.

In Red Dead Redemption, the key story beats remain the same throughout, but at what rate you take on the key missions is up to you. In between you can do what you like – you can get into a bar-room brawl, play poker, hunt wildlife or catch the attentions of local law enforcement.

Such open worlds fill themselves with the means for players to weave their own little stories against the backdrop of a wider narrative. The Elder Scrolls, Assassin’s Creed, and Saints Row series also do this, but to an even more open degree.

What Red Dead also exemplifies is how all aspects of a game can work as a cohesive whole in support of a story being told. Rockstar’s Western expanse was a barren, wild landscape that reflected its hero John Marston’s journey from desperation to losing himself and then finally to home.

Bioshock’s Rapture didn’t so much as reflect your own character as enforce the twisted madness of all the other characters. An underwater city as an insane place anyway, but throw in Big Daddys, Little Sisters, ADAM, EVE, and the Civil War that tore it all down and it becomes even madder – an oppressive, pressurized city that has already blown more than a few gaskets.

There have also been more experimental forms of narrative. Bioshock toyed with the habits of gamers, Braid played around with expectations, and the like of Limbo and Journey packed a wallop without even uttering a word.

Just this year Papers, Please has turned players into corrupt officials with the ability to save or crush fellow human lives. Gone Home was another to play with expectations but also toyed with largely unexplored themes.

The technology behind gaming is reaching a sort of plateau, meaning innovation will soon come from a more meaningful place. Developers will still strive to produce technical marvels and games of pure gaming bliss that don’t even need stories, and so they should! Alongside them however is a relatively new thirst for telling unique stories with real heart and soul.

Ben Skipper

Follow me on Twitter @bskipper27

-

A freelance journo with aspirations of becoming a games journalist, I've been gaming since the age of 7 when I first picked up a copy of Wave Race for my brand new Gameboy. A firm believer that Vice City is the best GTA, I'm less decisive about the favourite original starter Pokémon. Charsquirtasaur?