Imagine a world without physical limitations, a world where you can change anything about yourself, enhance it, improve it, augment it; a world where you could pay to make yourself stronger, faster, smarter, more resilient. Imagine a world where you could lose the use of your legs, your eyesight, your hearing, and have anything replaced or repaired with a modicum of effort, with a procedure no more complicated than a surgical operation.

What would you change about yourself if you could? If money was no object and technology no boundary? Would you enhance your muscle mass? Increase your running speed, sexual prowess, physical strength? Would you sacrifice your flesh for mechanical enhancements? And would you ever worry, even for a moment, that in doing so you might be sacrificing your humanity a piece at a time?

RETRO FUTURE: Consider, if you will, the world of Deus Ex: Human Revolution, Eidos Montreal’s gold-tinted prequel to Ion Storm’s now thirteen-year-old open-world role-playing shooter, Deus Ex. In Human Revolution’s dystopian 2027, the controversial science of human cybernetic augmentation makes it possible to “fix” anything you need to fix and enhance anything you want to – whether it needs it or not.

In this world – which shares themes and ideals with the universe of Bullfrog’s (and now EA’s) Syndicate – corporations rule. When money is God, whoever writes the biggest cheque sits on the throne, and the biggest business in the world is augmentation. Sarif Industries sits atop the pile, fighting off competition from Tai Yung Medical, their closest rival. In Deus Ex’s world, business is war, and both Sarif and Tai Yung employ their own private military companies to ensure their global stability. Even the UN keep peace with the help of Belltower Associates, a collective of PMCs that specialise in “urban pacification” and brutal crowd control.

Corporate tensions overshadow civilian unrest. Between those who see augmentation as the next – albeit artificial – stage of human evolution, and those who see it as an abomination against nature and humanity, there exists only a precarious, volatile middle ground occupied by those who never had the choice, accident victims who were “saved by science”, individuals augmented to preserve their lives at the perceived cost of their humanity.

ICARUS RISING: Protagonist Adam Jensen is rudely reborn to this middle ground as the game begins. After a tour of the Sarif manufacturing floor with his ex-flame, the lead bio-technician, Megan Reed, Jensen’s life is altered forever when augmented terrorists storm the building, and either murder or abduct the researchers and scientists. As head of security, Jensen intervenes, only to be beaten, shot and thrown clean through six-inches of glass. On a normal day, he’d be dead, but Jensen works for Sarif. He is resurrected, in a manner of speaking, only to find that he has survived at a great cost: So much of him has been replaced by cybernetics that he constantly questions if he’s even human any more.

The legend of Icarus is a major thematic element and it’s not a subtle connotation. Human Revolution equates the whole of humanity with that ancient Greek youth who took to the skies like a bird and flew too close to the sun. Man was not meant to fly, and Icarus – and by extension his father, Daedelus – paid the ultimate price. In Deus Ex those wings are augmentation, and the price is our humanity itself. It’s not only Jensen’s struggle to accept what he has become, but humanity’s struggle to maintain the advantages they have given themselves.

The drug Neuropozyne perpetuates and stabilises the bond between flesh and synthetic tissue – but brings with it its own side effects in the form of addiction and dependence. Those who choose the path of augmentation accept the path of Neuropozyne dependence right along with it, creating a whole new breed of junkie who isn’t only bloody-minded in his pursuit of the drug but is also augmented – enhanced – beyond the capability of normal man.

HARD WIRED: Despite the narrative’s dictation of Jensen’s initial rebirth and his reinstatement as a badass security operative, Deus Ex: Human Revolution is a game about choice. Four “pillars” support the gameplay and encourage you to develop a role and character for Jensen that fits your play-style and his place in this powder-keg world. Combat, Stealth, Social and Hacking are the primary disciplines, and every one has its place and purpose in Human Revolution.

Developing your Social augments, for example, allows you to become a (mostly) human polygraph machine. You can read stress levels, detect pheromones and generally spot a liar-liar by his pants afire just by asking the right questions. A great instance is an early mission that asks you to break into the Detroit Police Headquarters to recover the implanted neural-chip of one of the terrorists. There are several ways into the precinct, and the choice of access is all yours.

If you’ve augmented Jensen’s legs at this point, you could choose to vault over a dumpster down a side alley and sneak in through the back door. Alternatively, you can brazenly wander in through the foyer and attempt to talk your way past the guy at the desk – a conversation that could have repercussions later. Or, you could even walk up the porch and start blasting people to death, fighting your way to the objective in a hail of blood and bullets. Personal choice is hard-wired into everything you do, to the extent that the game can be completed without killing a single NPC (outside of the four intrusive boss fights), which means that murder is your choice. If you don’t have to kill, why should you? Why would you? Well, partly because Jensen is so well-equipped for it.

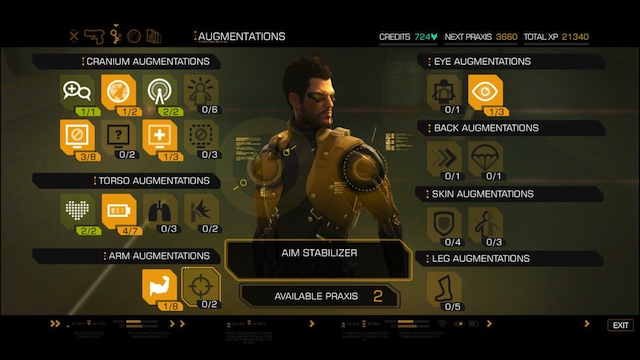

MORE THAN HUMAN: The augmented Jensen is a seriously mean motor-scooter, equipped with heightened senses, superhuman speed, increased strength and an arsenal of personal weapons concealed until he needs them. Retractable blades facilitate stealthy takedowns, strength augments allow heavy objects to be hurled at enemies, a tactical cloak refracts light around Jensen and renders him almost invisible to the naked eye. The integrated Typhoon weapons system transforms Jensen into a walking turret with a 360-degree field of fire. Choices, choices, choices. All augments are either awarded in the field or purchasable with “Praxis Points”, given in exchange for XP or bought at LIMB (Liberty in Mind & Body) Clinics found in the hub-cities. How you spend them is up to you, and you can respec at a cost should you wish to alter your play-style mid-game.

Sniper rifles, pistols, assault rifles, sub-machine guns and remote detonators provide the bulk of Jensen’s offensive arsenal and can all be upgraded when the need arises. Most missions will give you the option of taking lethal or non-lethal weapons (tazers and tranquiliser rifles, for example) with you from the get-go, but you can usually vary your tactics during a mission by relieving your enemies of their side-arms.

Quite often – as with most games that do stealth well – it’s more fun to go down the silent route. Sneaking around a domicile hotel in Hengsha while armed Belltower operatives go from berth to berth looking for you is a highlight. If you can make it out of there on Hard with no kills and no alarms (and I did), the sense of accomplishment is pretty huge. While the A.I. is sometimes a little unpredictable, the switch from first to third-person when you enter cover is a brilliant touch, perfectly combining the tense sneaking and creeping of games like Metal Gear Solid with the immersion of a first person shooter.

DARK CITY: There’s a certain realism to Deus Ex: Human Revolution that occasionally undoes itself. Hub cities that appear to be full of life and brimming with character come apart under close scrutiny. Reused textures and recycled areas rear their heads with regularity, the same three posters appear in the exact same position every few feet when in certain areas, and a break dancer in the subway performs the same moves to the same music for as long as you care to watch him are all particular low-points in an otherwise lovingly-crafted game.

Easter Eggs are abound too, referencing Philip K Dick and any number of Hollywood hits with equal cheek and charm, and there are so many small asides that you’ll always be finding something to do within the world. Multiple routes to objectives and some great level design sometimes clash with strange A.I. and glaring oversights such as those encountered within the aforementioned police station. Breaking in is tricky, but once inside you can simply stroll around without so much as a questioning look. I like to think it’s because Jensen was once one of Detroit’s finest and is recognised by his former colleagues – but who knows?

The complaints are minor though, becoming small niggles that pale alongside the overall quality of the gameplay. Like last year’s Dishonored, Human Revolution is a game that revels in giving you small-scale sandboxes to go nuts in. “Here’s your objective, here are your tools – now get it done!” The only disruptions to an otherwise smooth experience are the four boss fights. Formulaic, frustrating and restrictive, you’ve no choice but to tackle each with the heaviest weapons you’ve got in a dull game of pattern recognition made more “thrilling” by the possibility of annoying insta-death. And you’ve got no choice but to kill them all, which, given the freedom afforded elsewhere, just feels like shockingly lazy design. In Eidos’ defence, the fights were out-sourced to GRIP for development, but for many they were the soul reason that Deus Ex: Human Revolution didn’t garner more maximum review scores.

COUNTRY OF THE BLIND: The art style was never in question, taking cues from Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner but aping nothing. Blade Runner was a vision of the future of 1982, created in a time before the internet, before mechanical prosthetics, before the digital revolution; Deus Ex: Human Revolution is the future of now, a connected world that takes hours to circumnavigate, where technology is King and those who question its mastery are ostracised.

Human Revolution never pretends to be a realistic representation of our destiny, and the gold-hued artwork reinforces that. The whole game is draped in that honeyed sheen, juxtaposing the imagery of warmth alongside the ice-cold atmosphere of a world waiting to tear itself apart – the result is a game world that feels at odds with itself. More than that, the gold represents greed. This is a game that shows the most extreme possible outcome of consumerism, when corporations have amassed more wealth than world governments, when they are no longer guided by the fundamental concepts of right and wrong but only by the basest ideologies of profit and loss.

The world we’re shown is a bleak one, sure, but there is hope within it. Heroes like Jensen and Faridah Malik, visionaries like David Sarif and Hugh Darrow, and crusaders like William Taggart (leader of The Humanity Front, the biggest anti-augmentation organisation in the world) show that, even in a world beset by dreams of Godhood and global domination, plagued by terrorism and dogged by the hounds of uncertainty and fear, there are those willing to live, fight and die for what they believe is the greater good of humanity.

MAN OF THE PEOPLE: In fact, the characterisation in Human Revolution alone is indicative of the quality throughout. Jensen’s boss, augmentation magnate David Sarif, is a great character who could so easily have been turned into a 2-dimensional quasi-villain, just another megalomaniac with an agenda, but the writers do so much more with him. Not only is his respect for Jensen genuine, but his absolute belief that augmentation technology is the best and brightest future for humankind prevents him from ever being seen as a villain.

Jensen’s combat pilot and confidante, Faridah Malik, is another case in point. Their relationship occasionally strays towards flirtatious, but it’s born of mutual respect and loss. At a certain moment the narrative leads to Faridah making a crash-landing and being stranded in the centre of a gunfight, trapped in her gunship and surrounded by Belltower soldiers. The achievement or trophy awarded for saving her life is nothing compared to the sense of failure if your actions allow her to be killed, especially if you spent time talking to her earlier, learning about her character and relationship with Jensen.

Secondary players like Sarif’s resident tech-head and hack Frank Pritchard (outwardly a ponytailed prick, but actually a surprisingly valuable and reliable ally when the chips are down) and Hugh Darrow, the father of cybernetic augmentation who has come to realise that his own invention is destroying humanity instead of saving it, add depth and class to the world that goes far beyond the more straightforward sneaking and stabbing of the gameplay.

SEE THE FUTURE: Human Revolution is a game that deserved more recognition than it got. Lifetime sales have exceeded 2 million, but that just doesn’t seem enough. DLC in the form of The Missing Link went some way to righting the perceived wrongs of those awful boss fights, but the chances of a full sequel seem slimmer and slimmer with every passing month. While a movie has been green-lit, it’s hard to say whether or not it will ever see the light of day – and, if we’re honest, do we want it to? I, for one, would rather see another game, either as a sequel to Jensen’s story or perhaps revisiting the more distant future of the Dentons, the protagonists of Ion Storm’s original masterpiece.

Either way, the world Human Revolution presents and the questions it raises aren’t fully done with. Video games are, of course, fiction – and often fiction in the extreme – but scientists in the real world aren’t a million miles from their breakthroughs in limb replacement, a science that will surely lead into the investigation of the possibility of cybernetic enhancement. Would it be less far-fetched than Jensen’s universe? Would it be a less uncertain time to exist?

Deus Ex: Human Revolution was on my Game of the Year list in 2011 – and bear in mind we also saw Dark Souls, The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim, Uncharted 3 and Batman: Arkham City. The reason it was so playable then and remains so playable now, is its combination of incredibly versatile gameplay and provocative subject matter, delivered within the framework of a gilt-edged dystopia that represents the worst possible extreme of humanity’s future. If you missed Human Revolution first time around you owe it to yourself to give it play it through at least once. If, on the other hand, it has been a while since you last visited Eidos Montreal’s beautifully dark world, it’s worth replaying just to see what you missed last time. Deus Ex: Human Revolution is a genuine work of art.