The Story Mechanic Part Ten: The Business of Telling Tales

If you and I met, and provided I didn’t throw my drink all over you when you didn’t believe how “Bigtime” I was, eventually we would get talking about Portal.

Then I would tell you that the original game is better than the sequel; Portal is greater than Portal 2.

You would say that Portal 2, with its lengthy campaign and multiplayer, was a better total package and I would be forced to concede that small point. Then, for your impudence, you’d get another drink all over you as I explained that Portal’s single player campaign far exceeds the quality of Portal 2’s. Portal 2’s is longer, but fattier. Number two had the budget for name actors (who were tremendous), more levels and more backstory, but took the focus away from the perverse nature of GLaDOS’s relationship with the player which, in the first game, was like watching a salivating wolf smoothing a baby bird’s feathers.

What makes the Portal series so fascinating, beyond how wonderful both games are, is that their differences are defined by a business decision. The original Portal was a relatively cheap, high quality downloadable game. The game’s shorter length enabled the geniuses at Valve to write a tight, taut story that perfectly suited the title’s shorter length. Portal 2 was a full boxed release, priced at £40. That came with player (and reviewer) expectations. A single player quest can’t be three or four hours long when it costs forty pounds. Portal 2’s quest is far nearer to fifteen or twenty hours long. When combined with a brilliant multiplayer component, Portal 2 was clearly worth the outlay. However, fundamentally, the type of story that suits a longer game is different. The type of story Valve could tell had been altered. The laser focused interaction between player and GLaDOS that had powered Portal now would not be able to carry the full length of the new game. New characters needed to be introduced. New plot twists and backstory and objectives were needed to flesh out the player’s adventure. For me, Portal 2 lost something when compared to the abusive relationship between escapee and captor that defined the first effort.

The changes from Portal to Portal 2 are some of the clearest indicators of how the business of games affects the stories we experience as gamers. This isn’t unique to gaming, of course. Blockbusters are ninety minutes long because it is the sweet spot between customer satisfaction and the amount of screenings a cinema can do in a day. TV episodes are designed to fit snuggly into an hour with ten minutes of adverts. Comics have cliffhanger endings because the publishers need you to come back next month.

Until recently the only way to release a game was to make it a £40 boxed release. Yes, you could offer different genres and types of game but, fundamentally, player expectation was set and had to be met if studios expected to make money. This meant a certain length of quest and, in this way, a restriction on the types of story you could tell effectively.

Though it might sound obvious, different lengths of game suit different types of story. I believe that the growing downloadable games market is one of the keys to increased innovation in video game storytelling, building further quality and variety onto the sterling work that developers have carried out over the last few years.

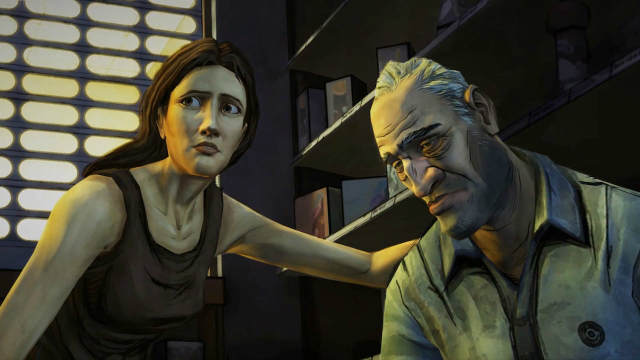

Telltale Games is an example of a studio leading the way, with their Walking Dead series. Everyone who I’ve spoken to has highlighted the series’ short games and episodic structure as one of the factors that makes it work. Players are left wanting more; the writing team can structure clear and effective cliffhangers where the drama builds outside the game as the player waits for the next instalment. Telltale is borrowing an established episodic structure (an integral part of the Walking Dead experience prior to the games release, whether you read the comics, watched the TV show or both) but have skilfully given it the uniquely gaming twist of persistent choices and cause and effect. The Walking Dead would be less effective if it was forced out as a full price boxed release. Every episode would have had to be published together in order to justify the forty pound price tag, leaving the sharp cliffhangers dulled as players rushed forward into the new chapter. If the player was denied the breathing space to discuss their choices with friends, or denied the time to have the emotional impact of the story percolate through them, The Walking Dead would be a lesser game.

Telltale have built a story structure to fit their model of distribution, and it is offering the player a unique and exciting experience which is getting a massive word of mouth following on twitter.

Contrast this with L.A. Noire or Alan Wake. Remedy’s game has a TV-style episodic structure (Sam Lake is on record as saying that the best way for games to deliver narrative was in bitesize episodes) but it is not really remembered for the effectiveness of these mini-cliffhangers because the player can barge right through them, onto the next section of the game. L.A. Noire, a game which deserves nothing but praise for its endeavor but that can be rightfully picked at over its execution, was another that was disadvantaged by gaming’s binary pricing culture. You have to invest plenty of effort in L.A. Noire; it is slow and rewarding, but it wears you out. You are constantly working things out and puzzling over clues. As the game draws to a conclusion you’re ready for it to finish because of the amount of time you’ve invested. It isn’t building to a glorious finale, it is grinding to the end, like climbing a mountain that gets steeper at its summit. L.A. Noire would have benefitted by being broken into episodes. It naturally breaks down by case desk, each one ending with a Phelps’ promotion and the enticing idea of new and more interesting cases (a move used by Chris Nolan at the end of Batman Begins, when Gordon shows Batman the Joker card). In my imaginary ‘Episodic L.A. Noire’, each desk would short and sweet, the player never tiring of the action. Rather than a single £40 release, L.A. could have been five £8 releases. Players who would have purchased anyway, enjoyed the experience more and the lower cost of entry entices more players to the game. By exploring these alternative distribution models studios can take risks, like the one taken by Team Bondi, and might find the end product easier to achieve. No longer would stories have to be compromised to fit business models; business models should be moulded to provide better stories.

Valve experimented with episodic content with Half-Life Episode One and Two. But could they have taken the experiment further? Would Half-Life 3 (if it dares to ever show its face) tell a more interesting, more intricate story if it was released as a number of short, parallel episodes, for example? Each could follow a main character, the stories could interweave and bounce off each other, filling out Valve’s world even further. A parallel example could be that of a DC or Marvel comic event, where many different books combine to weave an interlocking tale which draws the reader deeper into the experience. What is to stop a visionary studio like Valve producing and marketing their games in this way?

Innovation does not even need to be this radical. Let’s return to Portal 2 and re-imagine it. Rather than crowbar the two games into a single £40 package, why not release it as two separate games? Portal: The Robot Story (co-op) and Portal: Chell’s Story (campaign). Chell’s Story could be focussed to give the short, intense, involved story that a five hour downloadable title does so well. The Robot Levels could be released as they were, with all the potential for DLC still intact. Both could cost £10. Players could choose the Portal experience that they want and it would be all the better for it, as Valve wouldn’t have had to tweak their storytelling to fit an old-fashioned, arbitrary business model that doesn’t play to the strengths of their game. It’s just a thought.

The point is that games have the potential to be anything. By extension, the stories told in games have that same potential. Story is expensive though (cutscenes, actors, recording booths, writers) and so the business models to support building games with rich worlds and exiting stories has to be robust, profitable and, most importantly, flexible.

If companies could innovate with the way games are priced, constructed and sold, then I believe the types of stories that players experience would experience similar innovation. Companies needn’t force game stories to fit outdated, restrictive business models that have ingrained expectations onto the consumer. I hope that hardware manufacturers see this and, as we move towards the next generation, I hope that online pricing and distribution models reflect gamings myriad of options and unlimited potential. Then I hope studios take advantage of these opportunities

Then we could spend even more time being thrilled and surprised by stories in games. It would be just like the first time we all played Portal …

I told you that’s where the conversation would end up.