The Story Mechanic Part Three: A Conversation with Edmund McMillen

“For me, it’s less of a message and more of a conversation”.

Edmund McMillen hits on it easily and succinctly; stories in games are difficult. What makes them different from other media, what makes us demand so much of them, is that fundamentally they demand something from us in return. It is rare in TV, film or books that a story is so hidden from us that we have to actively engage in finding it. Characters and plots usually wash over us, pouring out of screens and pages like fast flowing water. In games, we have to succeed at something to be rewarded with story; kill a boss, master a technique, grasp a hidden meaning. We have to dig with our fingers for the tiniest drop.

However, it is precisely this interaction, in the mind of Edmund McMillen, that gives games a unique ability to not only tell stories but talk with the player and open them up creatively. When I asked him about the message he was trying to communicate with The Binding of Isaac, a game famous for its difficulty and commentary on childhood and Catholicism, McMillen was quick to explain that what was important to him was to get the player thinking; not to impart a literal message. “When you approach a video game and you are playing it, you mostly kind of approach it with the idea you are trying to solve a puzzle” he explained, “I think that if you approach what is perceived as this story in a similar manner then I think it gets that going in their heads”. Encouraging creativity is certainly a motivating factor for McMillen. One aspect of his growing mainstream fame and popularity is the scene in Indie Game: The Movie, where he is crying at the idea he has inspired younger generations creatively. It is exciting to think that he sees story as an avenue to inspire this creativity. What is interesting though, is that McMillen doesn’t consider himself a storyteller. He concedes, “I don’t think of myself as a storyteller because, I guess, it’s a non-traditional way of telling a story”.

So is Edmund McMillen just a game designer? Or is his non-traditional approach actually laying the foundations for future generations of game stories, as different as films are from plays and plays are from books?

McMillen believes that game narrative is at a “foetal stage”, with many in the industry experimenting hard with narrative delivery. His approach to crafting a game story is very open, attacking subjects which have inspired him or that he obsesses over with an open mind. “When I go in to tell a story, I don’t necessarily know what I’m going to say all the time” he admits. McMillen, who confesses that things don’t hold his interest for long, explores topics that he doesn’t completely understand because he finds them more interesting. “I’m not the sort of person who likes retelling the same stories, I want answers, and I want to know why”, he says. Short projects like Aether, which he worked on for “fourteen days” and is “really proud of”, allow him to explore many different topics and to collaborate with many different people. When asked if he feels any responsibility to the narrative ideas of these partners, he explains that it is different in every case, though he always loves the social interaction of making a game. He likens working with Tommy Refenes (his compatriot on Super Meat Boy) to a “marriage of ideas”, the two’s shared frame of reference allowing for a game design shorthand that makes it easy to implement the vision.

Whilst McMillen appreciates the contributions of those he works with, he is less thrilled by big business’ contribution to story in games. When discussing the similarities of big Triple A releases, McMillen laments that “sadly video games got swept up by business really, really, really early on”. The down economy, the risks associated with massive investment and the perception that successful games require huge investment to succeed, all contribute to an environment where too often companies play it safe and “playing safe means copying what works”. McMillen highlights Castle Crashers and Minecraft as games that prove small budgets and creativity can make for a financial success, but particularly singles out thechineseroom’s Dear Esther as a game that appeared out of the indie scene, was a huge financial success, and provided a successful interactive story experience. Here again, McMillen returns to the idea of player involvement – the conversation – as a key aspect of in game story; “there is a kind of definitive answer to the story [in Dear Esther], but really the way the story is told and experienced is pretty unique in the way it is left up to the player’s interpretation to figure it out as they go. The dialogue is basically like poems and you’re attaching the poems to things that you experience or read on the walls and they’re all kind of tied together with the music. You are drawing your own conclusions about what’s happening and why, and I think that’s really cool; and really special too.” It is high praise, of course, but it shows the consistency of McMillen’s design approach, placing high value on the player really contributing to their own experience, seeking out the game’s secrets and pro-actively attributing their own thoughts and conclusions to the patchwork of story information the game provides.

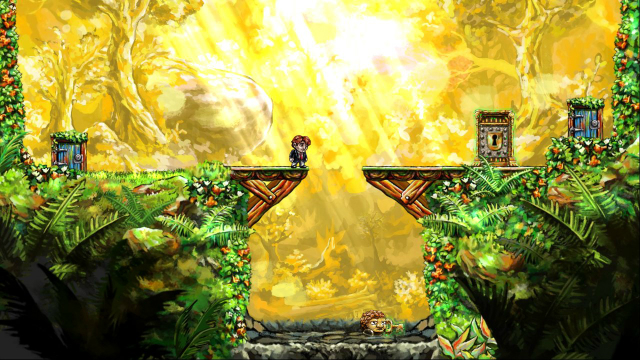

With this sort of experimentation and advancement there are inevitable success stories and failures. So where does McMillen see the real story development coming from? “Small Teams” is the key, in his view. Small teams from the indie scene have the advantage of not worrying about budgets and profits, with small teams in general having a “very tight and focussed vision”, able to attack specific problems and innovate with design. It isn’t a criticism of mainstream development, more an objective observation. With teams on triple-A titles often numbering hundreds of people, McMillen believes it is largely “impossible” to have the razor focus that is required to truly experiment in the burgeoning field of narrative development. He points at successful games like Braid as examples of a small team working on a title that wonderfully blends story and gameplay. In the case of the Braid, it is the rewind mechanic, as a metaphor for trying to correct mistakes in ones own life, that blurred the line between story and gameplay so effectively. Not as famous, but equally as affecting to McMillen, was dys4ia by Anna Anthropy (available here), a game about the designer’s transition from male to female. McMillen describes the game as “more literal” but still an “answer to the question that she was asked a lot”. With small teams, McMillen is adamant that “if you just kind of open yourself up and you are really honest with what you are doing, it is impossible to not have this really personal underlying theme happening in your work, even if you don’t intend there to be a story, even if you don’t intend there to be any kind of message or anything, I think it is kind of impossible to avoid the fact that you are still going to be kind of inside it; it is impossible for an artist to stop that”.

For all the artistic endeavour, it is not lost on McMillen that this industry, even when thinking about story, is driven by technology. His current interest, shown by The Binding of Isaac, is random generation. He compares random generation to a job he once had, which was largely menial but featured different challenges everyday. “There is something to re-rolling the day and not knowing what is going to happen, and how important it is in life to just enjoy life, the magic of improvisation and just not knowing and going in and playing it out”. McMillen believes in this idea strongly, thinking that it goes beyond games and that “random generation is the future of video games”. It feels like a strong statement, but McMillen sees this as a natural progression; “you could put it into most games, it would make things instantly replayable and just better overall”. McMillen’s description is exciting, and it is easy for the imagination to jump to a world where there is a Grand Theft Auto X, with a full city that generates random missions and random character arcs, the player the central character in a world that randomly formulates around their actions. McMillen’s current focus is more personal, trying to implement random generation into the games he develops even if “it is just to a small degree”.

Speaking to Edmund McMillen is an important reminder that story is just one part of a game, and not even a necessary part. However, his desire to have a conversation with players and to make games that engage them beyond what their thumbs are doing, illustrates the power that he believes story has. Game stories might not be traditional, they might still be embryonic, experimental and unformed, but they are an important way for game designers to express themselves and a growing part of games in general. What we can certainly deduce is that, even if Edmund McMillen still doesn’t see himself as a storyteller, he is certainly part of the conversation.